The events of the past two years have opened our eyes to many inequalities, and incited conversation on how we can begin repairing the impacts of discrimination and racism. What many of us forget is that a large topic left relatively unaddressed is the stigma associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

If you’re like me, perhaps you’ve spent the last year quietly passing judgment on the people who get COVID-19. It became a little too easy to lump everyone who gets sick into the category of “negligence”. Meanwhile, there are so many reasons individuals contract COVID-19, and a large part of those who are affected are those taking proper measures to stay safe.

Recently, I experienced my own “COVID scare,” and it made me realize how deeply this virus is rooted in stigma and discrimination, and why it’s crucial that we address it.

Why does stigma happen?

Stigma is a negative association related to someone with an illness. It usually stems from a lack of understanding, fear of being sick or dying, or the need to blame someone. This explains why stigma has been so pervasive during this pandemic. More than anything, people are scared for themselves and their loved ones, experiencing delays for things they need, or not being able to work or physically attend school.

After losing both of my grandparents to the virus last year, I got really obsessive about disinfecting and keeping everything clean. I would dry my hands out from frequent hand sanitizer application, wipe down every single food item with a Lysol wipe before putting it away, and do groceries alone to keep my parents isolated. I could feel myself getting weary of keeping my guard up all the time, but I knew those habits would be a more definitive way of staying safe. And then, it wasn’t.

A rude awakening: how quickly things can happen

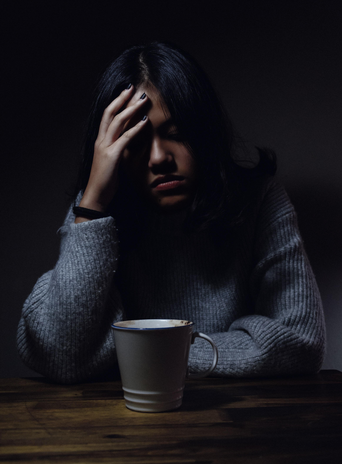

About a month ago, I came down with flu-like symptoms. I woke up shivering in the middle of the night, completely congested, and hot to the touch.

I went into a state of shock. I remember being so weak and cold one of the first nights that I couldn’t stand up by myself. My boyfriend had to walk me down the hall and run a bath for me, because I didn’t have the energy to do it alone. That night was really scary for me, because I was fairly certain that I had COVID-19, but didn’t know how I could have possibly caught it. Even worse, I had dropped off groceries at my parents’ place a few days before.

The day after I started experiencing symptoms, my boyfriend and I drove to a COVID screening site and got tested. The test was another source of anxiety for me, because I didn’t want to give COVID to other people getting tested, nor did I want to contract it if I didn’t already have it. Not to mention, I had heard stories of how unpleasant the test was. I’d had this idea that maybe I could go through the entire pandemic without getting sick and needing to be tested.

I can only imagine how many people contemplated skipping getting tested, or who never went altogether.

Stigma can cause people to conceal their symptoms and prevent them from getting proper health care, which contradicts healthy behaviours, and could put even more people at risk. No one wants to embody the fear or judgment associated with COVID.

Contrarily, the testing site was extremely well-organized and clean, and I felt that I was safe and keeping others safe the whole time. The nasopharyngeal test itself is unpleasant– you’d be surprised how far something can go up your nose– but it wasn’t painful and only lasted 10 seconds. My boyfriend and I got our results in under 24 hours, and both, shockingly, tested negative. That’s another thing: I think people are so caught up in COVID that we forget seasonal colds exist too.

Thinking back on it now, my cold was likely brought on by my lack of sleep and excessive studying. Trying to keep up with assignments while cohabiting for the first time and maintaining our new space really took a toll on me.

Fortunately, I think something about being sick at a time like this makes it easier to admit that we’ve all been subconsciously discriminating against those who get COVID-19 in some form or shape.

Why it’s dangerous to stigmatize

Stigmatizing those with COVID-19 perpetuates feelings of fear or confusion about the virus. These can also be internalized by the people fighting COVID, who end up feeling guilt or shame for being sick. The way society views an illness has a direct effect on the way people act when they contract it.

Though it’s important to be aware that your actions have effects on others, no one should be made to feel anxious for “getting others sick.” It is very likely to pass this disease on without knowing you did, simply because of how contagious it is, and the possibility that you are asymptomatic. Stigma about COVID acts as a barrier to treatment; it causes people to feel embarrassed or ashamed that they caught COVID in the first place.

This past year, stigma has also often led to discrimination or racism against certain minority groups, namely Asian communities, homeless individuals, those with underlying health conditions, and frontline workers. COVID has been referred to as the “foreign virus,” among many other derogatory terms, designed to pin the blame on a certain group of individuals. Individuals judged for falling ill often experience isolation, rejection, denial of healthcare or even housing, for example. This has caused many mental and emotional health repercussions for people who are sick at a time where they arguably need the most support.

Stopping the spread of misinformation and the epidemic of stigma will help make communities healthier and safer.

How to curb stigma

There are a few ways to prevent stigma, which can be enforced not only by our public leaders but also by ourselves in our everyday lives.

Firstly, address negative language or behaviours when you notice them. This could include tackling stereotypes and biases your friend or family member may have, spreading accurate information about the virus, and encouraging individuals to think about the issue from a more compassionate standpoint.

Secondly, remind those around you of the risk or lack of risk there is from being in contact with a certain place, person or product. This will reinforce healthy, safe behaviours while allowing people to go about a fairly normal lifestyle. Do research about mental health and social support services so you understand the options available to ask for help, and share these with those around you who you think may need them. Check in with your loved ones, make time for self-care, and keep yourself and others safe in public spaces.

Lastly, stop referring to people who contract COVID-19 simply as “cases”. We’ve had a lot of medical jargon thrown our way in the past 18 months, and while this may be good for understanding the virus in that sense, it also has a dehumanizing effect. Start thinking of people who catch COVID as actual people, because they are. They have families, a work schedule, hobbies, and lives, just like you do.

It doesn’t take very much to get sick even when you’re being as careful as you can. So, be safe out there, treat people with kindness, and try not to forget that we can only find solutions when we realize we’re in this together.