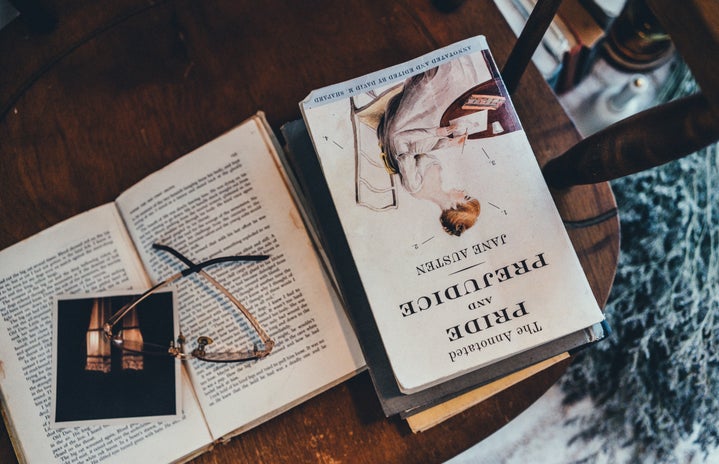

Admittedly, I hated classic literature when I was younger. Part of it definitely stemmed from being assigned the ‘hard reading’ group and muddling through the utter travesty that was ‘Red Badge of Courage’ in eight grade. Unsurprisingly, my animosity towards the archaic English language only compounded with a nearly unintelligible popcorn rendition of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ when I started high school. I simply couldn’t understand why self-pronounced bibliophiles would harp on and on about Jane Austen being the pinnacle of romance in classic literature. However, years of pestering coupled with the residual curiosity about why Mr. Darcy was so great culminated in me binge reading the most famous, and arguably most well-liked, Regency romance: ‘Pride and Prejudice’. My eyes were opened and I saw the proverbial light. Now, for someone who has never actually committed to a relationship, I have astoundingly high standards when it comes to all things romance. And once again, like every year, when this Hallmark holiday rolls around, I am reminded that I will never be the type to be satisfied by a wilting bouquet of roses and half-melted box of milk chocolate. How could I? Any respectable person would refuse to settle for less. At the end of the day, the blame lays squarely on the shoulders of one Fitzwilliam Darcy who truly started it all.

If you close your eyes for a minute, stop and envision the sunrise on an early morning. There are still fat dew drops on every blade of grass as a wispy blanket of fog obscures your feet, and to a degree it masks the figure slowly making their way across the field. They are haloed by the rays of the rising sun, unperturbed by the moisture slowly soaking their shoes and the overcoat that is dramatically billowing behind them. I am shamelessly alluding to Matthew Macfayden’s Darcy in the 2005 adaptation, but you have to admit it is quite a pretty picture. So what exactly is it that continues to captivate hopeless romantics, middle aged moms, spinsters, and cheeseballs alike? After binge watching the entire Bridgerton series on Netflix, plodding my way through half of Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton book series, and dedicatedly following every period drama I managed to get my hands on, I think I have a relatively good idea. Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy will always trump young adult literature supernatural heartthrobs and most other male leads of the romance genre. Here I stand, a self-proclaimed expert on (actually romantic) romance, and your tour guide for hot takes in historical fiction literature. But first, a bit of background!

When looking at Austen’s contemporaries and other novels of the Regency period, it is unsurprising that a lot of the conflict in the narratives revolve around the rigidity of class structure. Likewise, when examining the types of romantic leads in period literature, it is interesting to see how they are a reflection of this societal structure. Why do we idealize fictional men? What is it about these characters that appeals to us as real flesh and blood human beings? Unlike real people, we know at heart that the main leads and heroes in stories are good or will eventually reveal themselves to be good and worthy of love. They are reliably predictable in their change and the lack of variable unknown and lack of risk is safe. Moreover, stories allow you to explore and experience things you otherwise would not be able to in real life. The power of the imagination is something wonderful. That being said, when it comes to the Romance genre, the male leads are usually meant to fulfill a want and represent the solution to what may be lacking in the society of the author or the reader. During the Regency era, the social code of conduct was strict and incredibly limiting due to the gender roles of the time. Where women were not allowed to freely engage in their physical desires, or at the very least not expected to be open about it, there arises the stock character of the Rake. The Rake is passion and intimacy which wouldn’t otherwise be found in an arranged marriage whose sole function is the perfunctory production of male heirs. The Rake is representative of forbidden desire and recklessness. When marriages of the upper (literate) class were arranged for the sake of socio-economic ties in place of romance it only makes sense that real life was rather…shall we say lacking.

On the other hand, we have the slightly more respectable sort of the Byronic hero. Arguably, this is the archetype where Mr. Darcy may fit best along with other well known fellows such as Mr. Rochester from Jane Eye and the eponymous author of the trope Lord Byron. The Byronic hero is every bit the traditional counterpart to the feminine role of society as he is tall, dark, and handsome, as well as secretive, brooding, stoic, and silent. They nobly suffer rather than burden others and are rather self-sacrificing, especially when it comes to their romantic interest. Both of these larger tropes focus on members of the landed gentry who were often the biggest players of society both due to their immense wealth as well as status from decades and generations worth of respectability. This undoubtedly left only one alternative for male lead archetypes from such a strict social order: The Forbidden One. This is arguably less popular than the other two – largely due to the fact that the former present an escapist Cinderella-esque fantasy for many middle-class female reader, who much like Austen herself, was lacking in prospects and in want of a comfortable lifestyle. However, while The Forbidden One is lacking financially and in some cases in social standing, it appeals to readers who are tired of the formality of Regency era society.

Now, while Mr. Darcy undoubtedly fits the archetype of the tall, handsome, emotionally constipated Byronic hero, he has a certain charm to his narrative arc that sets him apart from other characters. The nuance and depth infused in his character development have yet to be properly replicated in any contemporary work, be it Austenian inspired or even corny dystopian romance aimed at teenagers. It brings in to question whether these paltry imitations even understand why the dynamic between Elizabeth Bennet and Darcy works so well. Contrary to popular belief, it is not your standard enemies to lovers slowburn with archaic language. The title of the piece is about as literal as it gets when it comes to establishing the theme of the book. Both our romantic leads are too stubborn and prideful to look past the early misconceptions they had of each other due to hasty judgements. Elizabeth realizes over time that Mr. Darcy is not a pompous rich git with a the proverbial stick of decorum shoved quite far up his…well you get the general idea. She, much like the reader, comes to understand that his actions reflect a rather blunt sincerity and incredibe amount of awkwardness around people. That hand flex scene at Pemberley, amirite folks. Over the course of not one but two proposals does Darcy show his worth as an equal worthy of Elizabeth Bennet’s affections. Notable examples of his growth include respectfully taking a rejection to his first proposal, helping the Bennet family track down Lydia after her brief and disastrous elopement, not expecting anything in return for aiding in the aforementioned situation, and what I consider to be the most important: actually changing when being told he had done wrong. Absolutely wild to think about these days, a guy changing for the better and committing to it for the sake of a relationship. Mr. Fitzwilliam Darcy is both rich and canonically attractive, but his appeal lies in the healthy amount of respect women juice in his personality.