An “invisible illness” is a physical or mental condition that is not immediately visible. It can range from ADHD to ulcerative colitis to diabetes; it is anything that you can live with for years and your friends would never know. It was not until a few weeks ago that I learned I had an invisible illness. Well, I’ve been ill for years, but I did not know there was a term for its imperceptibility.

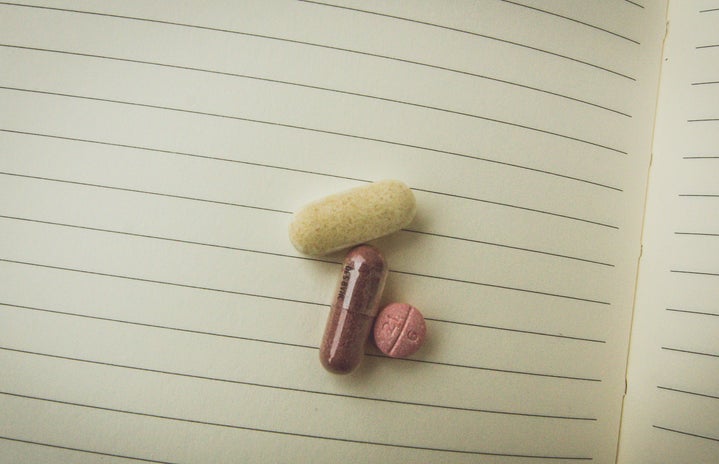

At the age of seventeen, I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease. It came at a time in my life when my physical health consumed the least of my worries, so I could not fathom the idea that I had my very own chronic illness. Luckily enough, my disease is a mild one and can easily be treated. I was immediately prescribed these big, red pills, which I had to learn to swallow. My first major challenge was that I had successfully traversed seventeen years of existence without swallowing a single pill. I now faced an ultimatum: swallow the massive pills and get better, or never learn to swallow them and continue living with the pain. I swallowed the pills.

It took me almost six months to accept the fact that I had a disease that was to live with me for the rest of my life. Doctors would poke and prod at me for the rest of my life. I would probably have to swallow those massive pills for the rest of my life. As an emotional seventeen-year-old, this fact rattled me. That became the year of understanding for me. Apparently, my mental illness was linked to my autoimmune disease. The reason I was perpetually exhausted stemmed from my autoimmune disease. If my body healed, my mind would follow suit. That is exactly what I needed.

None of my friends knew what I was going through until I fully processed it a year later. All they knew was that I saw an excessive amount of doctors and missed a decent amount of school. They did not ask for details and I did not provide them with any. Honestly, I never wanted anyone to know. Any form of pity or assistance repulsed me. I felt that the problem belonged to my body and myself, no one else. In retrospect, I attribute much of this thought process to my illness’s invisibility. It wasn’t a broken leg that everyone could fawn over. It was something deep in my body’s composition that made me feel disgusting. If no one else had to see it, then I would spare them that. At the time, I wish I didn’t see it either.

Four years have passed since that first diagnosis. I have been poked and prodded, I’ve become a master at swallowing those pills, and I’ve created an arsenal of doctor jokes. Most importantly, I am in remission. Though I feel significantly less disgusting, I still have not completely opened up to people about my illness. Only a small handful of my friends know, which is enough for now. Sometimes I still feel like I’m hiding something and I must remind myself that I am not. Visible and invisible illnesses each come with their own set of challenges, but one should not be preferred to the other. You cannot compare sicknesses like that. To be sick is to be sick. What I’ve learned is that you can also be a lot of other things in the meantime. You become incredibly skilled at the juggling act, at making things look easier than they are. You can share your illness with others if you want, but that is your choice to make.