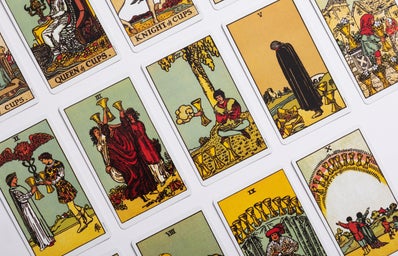

Users of social media may have noticed a new type of content creeping up in their feeds. Across TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram, a variety of content from the spiritual and the occult has permeated algorithms at a pace that is strikingly unusual. From crystals, manifestations, tarot readings, angel numbers, and to the rise of ‘Witch-Tok,’ practices once looked down on as taboo, hippy nonsense are entering popular dialogue.

Of course, the documentation and broadcast of spiritual practice is by no means limited to social media. In fact, representations of the occult, witchcraft, and spiritual practice have been floating around popular culture for some time. From series such as Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Buffy the Vampire Slayer to films like Twitches, Practical Magic, and Bewitched, film and television have long found success by fusing stories with the spiritual and the supernatural. The same carries over into music. Songs tapping into the theme of the mystic include Lorde’s ‘Mood Ring,’ ‘I Did Something Bad’ by Taylor Swift, ‘Which Witch’ by Florence and the Machine, ‘Black Magic’ by Little Mix as well as the witch symbolism in Beyonce’s album ‘Lemonade’ to name a few. There are even women such as Yoko Ono and Azealia Banks who openly self-identify as witches. With all this being said, it remains to be asked, what is the reason for the cultural fascination with the mystic and the spiritual?

Social science identifies this umbrella term of practices as ‘New Age,’ including everything from meditation and yoga to witchcraft and paganism. While these practices have always been present, it cannot be denied that although once reserved to the fringes of minority interest, they are now being practiced and interacted with at a much greater capacity. It is difficult to pin down an exact explanation for this increase, but there are several factors that might prove significant.

Firstly, it may not be a complete coincidence that this heightened interest in the mystic and spiritual overlaps with the timeframe of the ongoing pandemic. In a period of prolonged uncertainty, people may have found comfort and security in the divine guidance of angel cards, meditation, and crystals. Alternatively, perhaps this interest in the spiritual was already circulating prior to the pandemic, and like other mundane parts of normal life like work and university, this is just another activity that has moved to the digital landscape.

It may also be argued that this hunger for the spiritual is simply an extension of the wellness movement. Some might argue that they practice meditation and yoga in the spirit of wellness, unaware of their ties to spiritual practice. While there is no right or wrong way to practice either of these, the examples of yoga and meditation beg the question of what exactly separates the cultural threads of wellness and spirituality, if anything at all? Although one might associate wellness with images of healthy living and self-care, who’s to say any of this doesn’t correlate with the intentions of spiritual practice? Perhaps meditations are simply the new potions of the modern-day witch, and a yoga mat her new broom?

It should not be overlooked that the popular, aforementioned image of the witch riding a broomstick (with a black cat and pointy hat) does not exactly have a legitimate background. In fact, throughout the Middle Ages–far from anything supernatural–witches were ordinary women. What made them witches was their tendency to stray from the cultural expectations for women of the day–by living alone, not being present in their locality, not going to church, not bearing children. It is hard to ignore that these are now commonplace for women, which leads to a second possible explanation: are women tapping into the spiritual as a source of empowerment? Empowerment does not translate to political, but it is interesting to consider the involvement of groups such as during the second wave of feminism. The Goddess Movement was heavily concerned with the reproductive rights of women during the 1960s, and one group at the centre of this movement was W.I.T.C.H in New York. Using guerrilla theatre, they embraced the ‘wickedness’ of womanhood in an effort to affect change in corporations they believed to be preventing the liberation of women.

It is impossible to know for certain what it is about spirituality and the occult that has fuelled its revival in contemporary society. Perhaps it is explained simply by access to information online, or perhaps it is representative of a deeper cultural movement like that of the Goddess Movement of the 1960s. Regardless, it is clear that we are fast moving away from a time when knowing your zodiac sign or owning a dream catcher was questionable.