One subject we have been discussing in my Race, Representation, and Law class, is how the law is not a fixed or neutral entity, instead law is shaped by the people in power, which in turn constructs the legal contexts we see enforcing discrimination.

We read a book, Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine, by Noura Erakat who describes the nature of law really well through an analogy to a sailboat. She explained how the law is like the sail, with guaranteed motion but uncertain direction.

This indeterminacy of law means that law itself is not synonymous with justice, but can be used as a tool for justice or injustice.

One historical instance of law being used for injustice is represented when analyzing the Ruffin V Commonwealth case of 1871. This case was between prisoner Woody Ruffin and the commonwealth (aka state) of Virginia. It was sparked after Ruffin killed a guard during an attempted escape from the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, where he was leased to provide forced labor.

The case was not about the killing however, it was about whether Ruffin deserved a trial due to his status as a prisoner. The supreme court of Virginia ultimately decided that he had lost his rights and opportunity to a fair trial when he became a prisoner. This decision was monumental in setting unjust legal standards regarding prisoner rights in America.

It set the precedent that it was acceptable to treat prisoners as sub-human with no rights. It also claimed he was “civically dead” and thus also had no rights available to him after his sentence in prison. From this point on, prisons applied this concept of rights forfeiture, where prisoner’s constitutional rights and protection were given up as a punishment for committing a crime.

This discriminatory law lasted for almost a century until 1974 when the Wolff V McDonnel supreme court case acknowledged that prisoners should have rights. However, prejudice against prisoners remains set in stone in our nation. While the law has acknowledged the unfair nature of rights forfeiture, most prisons have maintained the horrific conditions and treatment of prisoners during their sentence and when they attempt to re-enter mainstream society.

According to Penal Reform International, an organization dedicated to restorative justice, overcrowding is one of the major challenges today. They state that, “Prisons in over 124 countries exceed their maximum occupancy rate, which results in violence, higher rates of death in custody, a lack of healthcare provision and low rehabilitative opportunities.”

This is undeniably true in the U.S. as we are home to 1/5 of the world’s prisoners at 2.2 million people. The status of prisoners impacts the rights allocated to them even after they leave, as it severely limits their chances of buying a house, receiving a quality job, and participating in society at large.This creates a generational impact that perpetuates the racial wealth gap and allows the cycle of mass incarceration to continue.

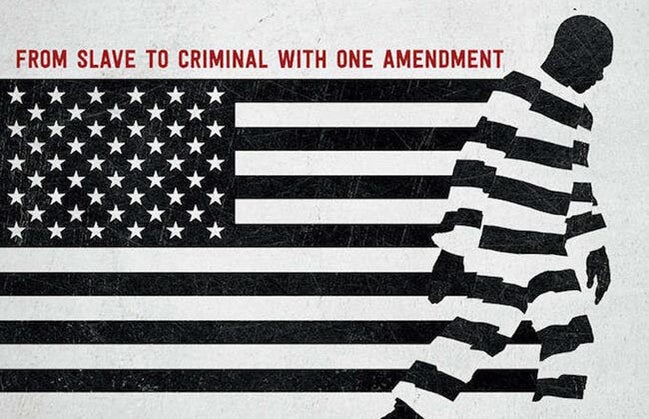

When the Ruffin V Commonwealth case is paired with the 13th amendment, a destructive new form of epistemology surfaces.The court declared that for the time being Ruffin was a “slave to the state”, which they were able to claim because of a loophole left in the 13th amendment.

The 13th amendment is historically known as the amendment to abolish slavery, but there is a clause in the middle that allows an exception for slavery to continue through prisoners.

The amendment states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

So, while at first glance it seems that the 13th amendment ended slavery, further reading shows how it did not end slavery, but instead let slavery continue under new conditions, criminality.

This amendment was passed in 1865, a mere six years before Ruffin V Commonwealth went to the Virginia supreme court. This case was one of the first that applied this loophole and took advantage of prisoners for labor, thus beginning a new legal framework for slavery.

Kevin Gannon, one of the scholars included in Ava DuVernay’s documentary, 13th , (which you can watch on Netflix) points to the reason why incarceration is considered slavery in an interview with Democracy Now! He states, “Slavery is a state of profound unfreedom, of not being an autonomous individual, being owned and subjugated under another.”

This distinctly fits the nature of prisons and the power structures at play there. The dynamic between White guards and Black prisoners remains eerily similar to that of the dynamics between masters and slaves. For instance, in 2018 Time published an image of an 1850’s slave owner atop of a horse watching over slaves pick cotton. When placed next to a modern image of an Angola prison guard, again on a horse, watching over prisoners as they do labor in the fields, it is clear that slavery is alive and well in our world today.

This reconstructed form of slavery was in turn, a new way to control Black bodies and perpetuated the criminalization of Blackness. Immediately after these legal precedents were set, Black people were systematically placed right back on the cotton fields and in other areas of labor.

One way this was carried out was through the implementation of vagrancy or loitering laws. Black people were often charged under these laws for little to no reason backing the claim. Law enforcement officials could use this as a justification to charge as many people as they wanted in order to continue using Black bodies for labor, and to maintain hegemonic control over them in society.

Vagrancy law is one example of how even a small unseeingly brutal law can be used as a tool for injustice. Over the past century, vagrancy laws have for the most part become obsolete, but new strategies have been put in place to streamline Black bodies into prison such as rhetorically clever campaigns like the 1980’s war on “drugs” and “crime”, as well as other masquerading terms like “law and order”.

Marijuana use, for instance, is used at similar rates amongst all races, yet Black people are unfairly charged for even the smallest case. According to the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI), one in five prisoners in the U.S. today were placed in prison for a drug offense, the majority of which were non-violent. In fact, the PPI states that “450,000 are incarcerated for non-violent drug offenses on any given day”.

These campaigns along with other discriminatory elements within the criminal justice system has created a culture of mass incarceration where Black individuals are disproportionately serving time behind bars.

So, while our laws may seem neutral at first, further analysis uncovers how embedded they are as tools of power. Our modern incarceration system was created and molded into a system of controlling Black bodies, so our nation needs to make a structural change in order to restore our justice system. While this is daunting, we as a society have the ability to change our structures and liberate law as a tool of justice.

Sources & Resources to Learn More:

https://innocenceproject.org/13th-amendment-slavery-prison-labor-angola-louisiana/

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/09/prison-labor-in-america/406177/

https://www.prisonstudies.org/news/more-1035-million-people-are-prison-around-world-new-report-shows