When you were young, did you have a single garment that you refused to be without? A shirt, pair of socks, or jumper that felt like an extra appendage and served the sole purpose of comfort, one that your parents would negotiate with treats as an incentive to take it off? For me, it was a purple bowler hat, with three felt flowers, blue, pink, and yellow, stitched on the side. My mom got it for me from some fancy children’s boutique, and although it was ridiculously overpriced, I got my money’s worth by never taking it off between the ages of four and six. Regardless of temperature, occasion, or color scheme of the rest of my outfit, I always had that hat on. I thought it made me look sophisticated, and somewhere in my soft, innocent-tiny-person brain, I thought that sophistication was the key to earn respect and friendship on the preschool landscape. Aside from that, it covered up the snarls in my hair that I refused to let my mom brush through.

On one day in particular, when I was in first grade, I got a terrible headache. While sitting at my desk, practicing print handwriting, I realized I’d been having this same headache for a while. Each day, I’d find myself struggling to keep my head up without pausing to pinch my temples. When I came home from school that evening, and went to pull the hat off, I noticed a pink, patchy stripe of inflamed skin that connected one temple to the other. I ran my fingers along it, noticing it was sticky with sweat. I was instantly overwhelmed with concern. What if my headache is a symptom of a freakish sickness that has seeped out of my forehead and onto my skin? I called out for my Mom to tell her the news. She laughed, smoothed out my hair, and assured me that I wasn’t sick at all. Her diagnosis was much worse.

“It looks like your hat is getting to be too small.” She picked up the hat and placed it in our running donation pile. “It was about ready to be retired anyway.”

To her what was nothing more than the cycle of clothing life, was to me an earth-shattering, heart-wrenching revelation. I wailed uncontrollably, insisted it still fit, and smushed it onto my head, ignoring the sting of fabric compressing my blood vessels so that I could prove her wrong. She promised we’d find a new hat that I would love just as much; we’d go find one at the mall that weekend. It would all be fine.

The only problem was that I didn’t want a new hat. I was convinced that, regardless of how many shops we prowled around or magazines we flipped through, there wouldn’t be a hat that could be better, even if its radius was equipped to wrap around my head, with wiggle room to spare. This hat had walked around with me every day for years and had its own place in my closet. Hell, it had soaked up hours and hours of my head sweat into its fibers! Is that gross? Probably, but it still provided me with a sense of comfort that carried me through my days, one that I couldn’t find anywhere else. It wasn’t as simple as not wanting a new hat, it’s that I wasn’t capable of having one. This “new hat” simply didn’t exist.

You’re probably thinking, All this over a hat? Seriously? This girl is so spoiled and materialistic! Believe me, I know how it sounds. But, we all have our own purple bowler hats, many actually, and they come and go without warning.

We are creatures of habit, and the very thing that makes habits so handy is the same one that makes them dangerous. Think about learning your multiplication facts. There was a point in time when numbers were nothing to you but curves and lines connected on a page, and now, after sitting down night after night at the kitchen table reviewing them with worksheets and flashcards, you’re able to add them with each other, take them away, multiply them to the power of another. The habit of reviewing and tossing them around in your brain slowly built strong roots that tied you to a concrete idea of how things are. Four times four is sixteen, three times three is nine. These roots go deep into your subconscious, into the collection of what you know to be true, and they grew with the simple nourishment of habit. See, magic!

Now think about the food you eat. Let’s say one night you have a healthy dinner, full of vitamins and nutrients and protein and all the other stuff you’re supposed to have on your plate. Then, for dessert, you have an entire pint of Ben & Jerry’s while you binge watch episodes of Big Little Lies you’ve already seen three times over. It’s a necessary act for days that are particularly hard, or when you want to reward yourself after a long week.

But then, you do the same the next night. And the next night. And the night after that, until you can’t eat dinner without gobbling down a mound of Cherry Garcia right after. Those same roots that grew when you ran through multiplication problems run through you in this instance too, but the results are a little more disheartening. The sourness of sugar withdrawal plagues you when you try to ignore cravings, lethargy follows you throughout the day, climbing stairs makes you feel as though you should be accompanied by an oxygen tank. Nourishing indulgence with habit is bad for your body, and it starts to show through how you feel. Not as helpful as multiplication facts, right?

Habits can be relieving, because they help expedite the process of achieving our goals, and give us some semblance of control over our lives in a world that does whatever it wants with us, without an ounce of remorse. These roots that habits grow inside of us provide security, but what happens when the habit grows into something that doesn’t make us better? Snipping those roots is excruciating. And who wants to be in pain?

When I was forced to give up my hat, I wasn’t really distraught because I loved the way it looked on my head. In retrospect, it was actually kind of ugly, and made me look like a cartoon television program’s token best friend who is known for her tacky outfits. The real reason I was so against giving it up was because the roots that grew from the habit of wearing it each day made it a part of who I was. I was chubby-cheeked, loud-mouthed, hazel-but-sometimes-green-eyed Olivia, with a purple bowler hat atop my head at all times. My resistance to taking it off wasn’t because I thought it was a beacon of fashion, it was the fear of not knowing who I would be when I did. Would I be the same? Better? Worse? Being rootless, untethered from the ground and my place in the world, was scary. As I got older, I had iterations of the purple bowler hat present themselves to me in the form of hairstyles, jobs, homes, people. And each time I had to “take it off,” it felt like the stakes got higher.

I know me as I am now, with the job I have, the home I drive to each evening on the commute I’ve made a dozen times over, the hobbies I do under the light of a dim lamp after eating one of the few dinners I can make that is cheap, healthy, and doesn’t taste like cardboard, the friends I sip wine with on the couch who have known me since I was an awkward middle schooler. But what happens when the job you have doesn’t provide you with the benefits you need to live, the hobbies you do don’t fill you with tingles of joy like they used to, or your friends start to feel less like friends, and more like strangers that you’re making lackluster conversation in a shitty attempt to keep things lively?

Snipping those roots that have caused you to become accustomed to one way of living means looking up to something else. But what if there’s nothing there? What if your years of life experience haven’t given you enough horsepower to switch gears? What if you got lucky in seventh grade, and the friends you have now are the only ones you’ll ever find who will put up with your weird quirks and annoying traits? Sometimes the fear of not liking who you will become outweighs the discomfort of staying as you are, even if that means headaches and constricted blood flow that spreads itself right across your forehead.

In the initial aftershock of getting rid of the hat, I mourned. I started wearing my hair in a tight ponytail at the nape of my neck in protest, although it made me look like some sort of Colonial-age Postman. I never forgot the hat, or the way it made me feel, but something changed that allowed me to look up and away from the broken roots in front of me.

Halloween came.

While all the other girls went as Lava Girl or Hannah Montana, as those were the iconic female characters of the year, I dressed up as a 1950s Car Hop Waitress, complete with the pink ruffled apron and black and white saddle shoes. It wasn’t so much that the 1950s aesthetic interested me, but that the outfit came with a pair of non-prescription cat-eye glasses, equipped with fake jewels on the sides. Although I didn’t have any vision impairments at the time, I decided I needed them. I begged my Mom to buy me a pair without the costume, because truth be told, I really wanted to be Hannah Montana instead. She insisted it was a ridiculous thing to buy, and if I wanted them, I’d have to get the complementary ones that came with the costume.

I really wanted those glasses.

So, I let my Mom tease my hair into an obnoxious side pony, I pulled on the scratchy poodle skirt, and you had better believe I marched around my neighborhood with pride on Halloween night as a 1950s waitress, to which passive-aggressive neighborhood Moms giggled at me and told me how precious I was.

Putting the glasses on felt like magic. Even if they were nothing but plastic that rested on my nose, there’s something about having control of the self you present to the world, of which clothes and accessories are most definitely a part, that gives you an overwhelming sense of power. Wearing the glasses gave me the same delight that the purple hat once did, so much so that I never took them off, either.

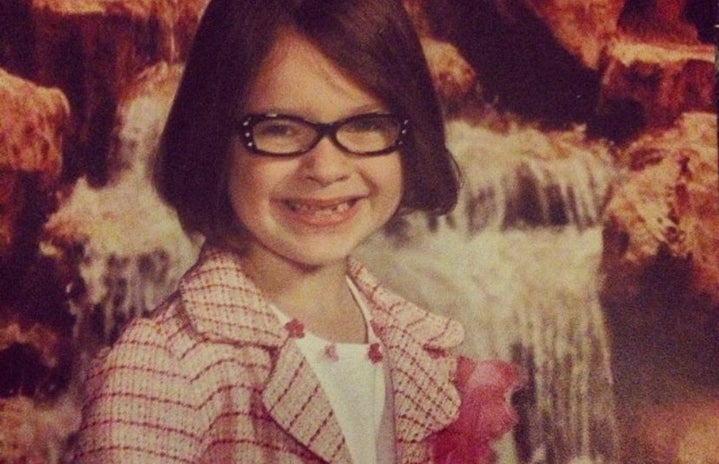

Above is my first grade spring picture. When I look at it, I not only see an ugly backdrop (why my Mom picked a waterfall straight out of an antidepressant commercial, instead of the cool multicolored lasers option, I will never understand), but also an obnoxiously confident and proud seven-year-old. My new glasses led me to try things I wouldn’t have before, including wearing skirt suits, such as the one I am wearing in the photo. The hot pink tweed ensemble, which is reminiscent of something a proud grandmother would wear to a high school graduation, or an overly-perky real estate agent to an open house, was something I put together all on my own.

“Are you sure you don’t want to wear a sundress, or your sparkly jeans, or the cute angel kitten shirt I just got you?” My mom asked as we reviewed outfits the night before. I was determined that the skirt suit was the right move, mostly because it was the only thing in my closet whose refinement matched that of the cat-eye glasses, which I, of course, had to wear. They were a part of me, after all.

Whenever I start to feel growing pains in an aspect of my life, I can’t help but feel overwhelming fear that manifests into a mound of lead at the pit of my stomach, or even uncontrollable tears that trickle down my cheeks. No matter how evolved or self-aware you are, it never gets easier to snip the roots of attachment, even if it’s something that isn’t good for you anymore, something that doesn’t fit.

But, when I do catch myself feeling this way, I remember Halloween. I remember the way the poodle skirt made my butt chafe and the way the glasses made up for all of it. I can’t imagine who I would’ve been without the glasses, who I’d be now. If I hadn’t gotten rid of the hat, I wouldn’t be able to put them on. After all, there wouldn’t be enough room for both on my face. The hat’s brim hung too low.

Letting go of things is hard. Having the pragmatism to recognize what’s good for you, and what isn’t, takes work. And finding something new you love just as much doesn’t mean replacing something else you loved before or trying to recover a comfort that isn’t meant for you anymore. But, if we don’t go through the pain of cutting the roots that have attached us to a self we don’t want to be, we may miss the opportunity to be planted somewhere new, somewhere that means new experiences, new relationships, new interests and skills we didn’t know we could have. Reinvention is ambiguous and scary, but doesn’t ambiguity have a connotation of excitement, too?

To this day, I still have a pair of cat eye glasses with jewels on the sides, although they are prescription now. And when I have a day that I need a little boost or re-centering, I’ll pull them out. They hold the same significance as the pair I wore in my school picture all those years ago.

But, the inevitable day will come that my prescription will shift to the point that I need a new pair. And by then, it will be time to trade them in for a new style. Maybe I will go for the thick-rimmed tortoiseshell look, or metallic white frames that make me look like a hot-shot Silicon Valley exec, since those are all the rage these days. Either way, the cat-eye glasses, same as the purple bowler hat, will be put into the donation pile eventually. And I’m learning to become okay with that more and more every day.