The site OnlyFans burst into mainstream attention with the beginning of lockdowns around the globe as COVID forced us to stay inside and move our lives, and for some, their careers, online. Despite being used by a range of other content creators and professionals such as fitness trainers, musicians and fashion influencers, we mostly associate OnlyFans with sex workers as it is the only social media platform that allows nudity and sexually explicit content.

So, the site is no stranger to naked bodies, but you might be surprised to find that some of the bodies subscribers pay to see are pretty old… and I’m talking hundreds of years old. Oh, and they’re also from famous works of art.

When trying to advertise a series of new shows on multiple social media platforms, the museums of Vienna were surprised to find that time and time again, their posts were removed due to nudity rules. In July, the Albertina Museum’s TikTok page was first suspended, then entirely blocked, and the Leopoldo Museum had a Facebook video of Koloman Moser’s ‘Lovers’ painting removed.

There are plenty more examples, the worst of which is perhaps the Natural history Museum’s image of the Venus of Willendorf figurine, which was removed by Facebook, despite being roughly 30,000 years old. So, in defiance, Vienna’s tourism board launched their new campaign, playfully named “Vienna Strips on OnlyFans.”

Helena Hartlauer, speaking on behalf of the tourism board about the nude artworks, told the Guardian, “these artworks are crucial and important to Vienna [….] If they cannot be used on a communications tool as strong as social media, it’s unfair and frustrating. That’s why we thought [of OnlyFans]: finally, a way to show these things.” They hope their efforts will not only boost the slumped number of tourists to Vienna, but also draw attention to how much difficulty censorship causes artists.

Facebook and Instagram have enormous power to control artistic expression by taking down artists’ work from their platforms, removing their access to a really important audience, literally billions of users.

This issue was first brought to my attention last summer by Alex Cameron, a photographer who specialises in female portraits celebrating body confidence. She’s always looking for women to work with who “present themselves so boldly online it can inspire people, make them feel less alone, empower them and encourage self-love”.

She reached out to Nyome Nicholas-Williams that summer, a plus-size black model, who fits this description perfectly (a quick scroll through her Instagram will not disappoint, I promise). They did a photo shoot, and, delighted with the results, both shared some of the images on Instagram.

However, the photos were taken down, despite Cameron having reassured Nicholas-Smith that she had “photographed [herself] wearing less and posted it, […] and those images were staying up.” They kept reposting, assuming there had been a mistake, but the images were relentlessly removed.

The situation only gets worse when you consider that accounts such as Playboy and many others have photos that are far more explicit which aren’t being taken down. Not everyone is affected by censorship rules in the same way. The bottom line is that generally thin, white bodies just aren’t being hit with the same strict rules.

Nicholas-Williams posted on Instagram, “why is my body always being censored!? It’s always Black women with bigger bodies and I am trying to normalise ALL body types and I keep getting shut down at every turn.”

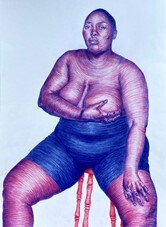

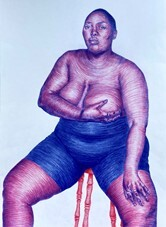

So, they teamed up with Gina Martin (the activist and artist responsible for making up-skirting illegal) and started the #IWantToSeeNyome campaign. They used their platforms to spread awareness and asked followers to repost the images or their artwork from them. This was when I joined in and drew one of Cameron’s images, posting it on my account with the hashtag.

Lots of others did the same, #IWantToSeeNyome caught on and the discussion grew, gaining press attention as it snowballed until it became a campaign fighting against sexualisation and the censorship of female bodies, especially for black, plus-size women.

These three women have shown that it is worth our effort to fight back though because Instagram finally acknowledged their errors and began discussions on how to improve. They have promised to reassess their AI and manual teams policies on what is classed as ‘pornographic’. They will now allow content where someone is hugging, cupping or holding their breast.

When VICE UK reached out to Instagram for a comment in early October, a spokesperson confirmed that Instagram had “apologised directly to Nyome for repeatedly removing her image”. They added that “this shouldn’t have happened and we are committed to addressing any inequity on our platforms.” The issue is nowhere near solved though and attitudes towards women and female-presenting people’s bodies still need to change enormously.

I’m sure many people don’t understand what the problem is. If these platforms don’t allow explicit content, why shouldn’t they remove images they deem to be inappropriate?

The problem is that censorship and what is deemed acceptable or not is so deeply rooted in misogyny (as well as many other intersecting factors). Women’s bodies are constantly shown in sexual contexts in mainstream media and advertising, but overwhelmingly as the object of male desire. The female body is used again and again as a symbol of male wealth and power.

Sadly, it’s often when women take autonomy over their own bodies and use them in art or activism that the images are removed. They are disrupting the accepted narrative that their purpose is to please men and to look a certain way, and that is at the heart of what makes viewers find them ‘uncomfortable’.

By censoring female bodies, we label them as something bad, something which must be hidden. It perpetuates the sense of shame that is detrimental for our mental health in terms of our relationship with ourselves, and also the taboo around studying our bodies which has created a shocking gender health gap.

There has been five times the amount of research into male erectile dysfunction compared to premenstrual syndrome, which affects ninety percent of people with female reproductive systems, compared to the latter affecting only nineteen percent of people with male reproductive systems.

We need to demystify the female body and to do that our bodies must stop being seen as inherently sexual and a taboo subject. Loving and understand our bodies will remain a challenge until society begins to see them in a radically different light.

Louise Brown, an artist whose feminist illustrations were censored by Newcastle University, wrote: “people need to see depictions of bodies that are not in line with dominant beauty standards. Hiding feminist artwork in the face of media and other outlets bombarding young people with a single, restrictive and quite frankly unattainable standard of so-called ‘beauty’, is a dangerous move. Vast depictions of the female form should be in our day to day lives in order to counter the mainstream, in order to prevent eating disorders and negative body image.”

Yes, censorship of the female body on social media exists because of deeply ingrained societal attitudes, but that doesn’t mean that those same platforms can’t be a crucial weapon in fighting back against misogyny. They can be a space that allows women and girls to support and celebrate each other. They can be used to counteract the harmful effects of images we are exposed to in advertising and the media of a single ‘ideal’ body type, but this isn’t possible without censorship reform.

Words by: Olivia Burnett

Edited by: Yasmine Moro Virion