The pain that accompanies my chronic illness comes in waves, and last summer was a particularly painful time for me, both physically and mentally. In the six years living with my illness, it finally dawned on me that I was utterly alone (at least it felt so). My doctors practically told me they had run out of ways to help, leaving me to my own devices. I had to try to fix myself.

Before once again attempting physical fixes, I decided the more urgent matter was a mental fix. I needed to feel less alone. I needed to know someone else felt this way. I needed to hear another story. Naturally, I Googled “best books about chronic illness.” Very few helpful resources presented themselves. I didn’t want to read another memoir full of horrifying anecdotes or a self-help book ridden with elaborate recipes—I wanted a novel. Where are all the fictional accounts of chronic illness? Are there even any? People have been sick since the dawn of time, and I knew there were novels out there portraying sickness if only I could find them. Hence, my search.

I have cobbled together a small list of novels—almost all of them I’ve discovered since last summer—which helped me come to terms with my chronic illness in some way. Not all of them talk about chronic illness and pain explicitly, or in the language we use today, but I believe they are accurate representations nonetheless. I also want to emphasize that these novels feel representative to me and my illness, and I do not mean to speak for others or claim that all illnesses look how they do here. I’m making this list because I wish I had it six months ago and, in case someone else is Googling, hopefully this article presents itself.

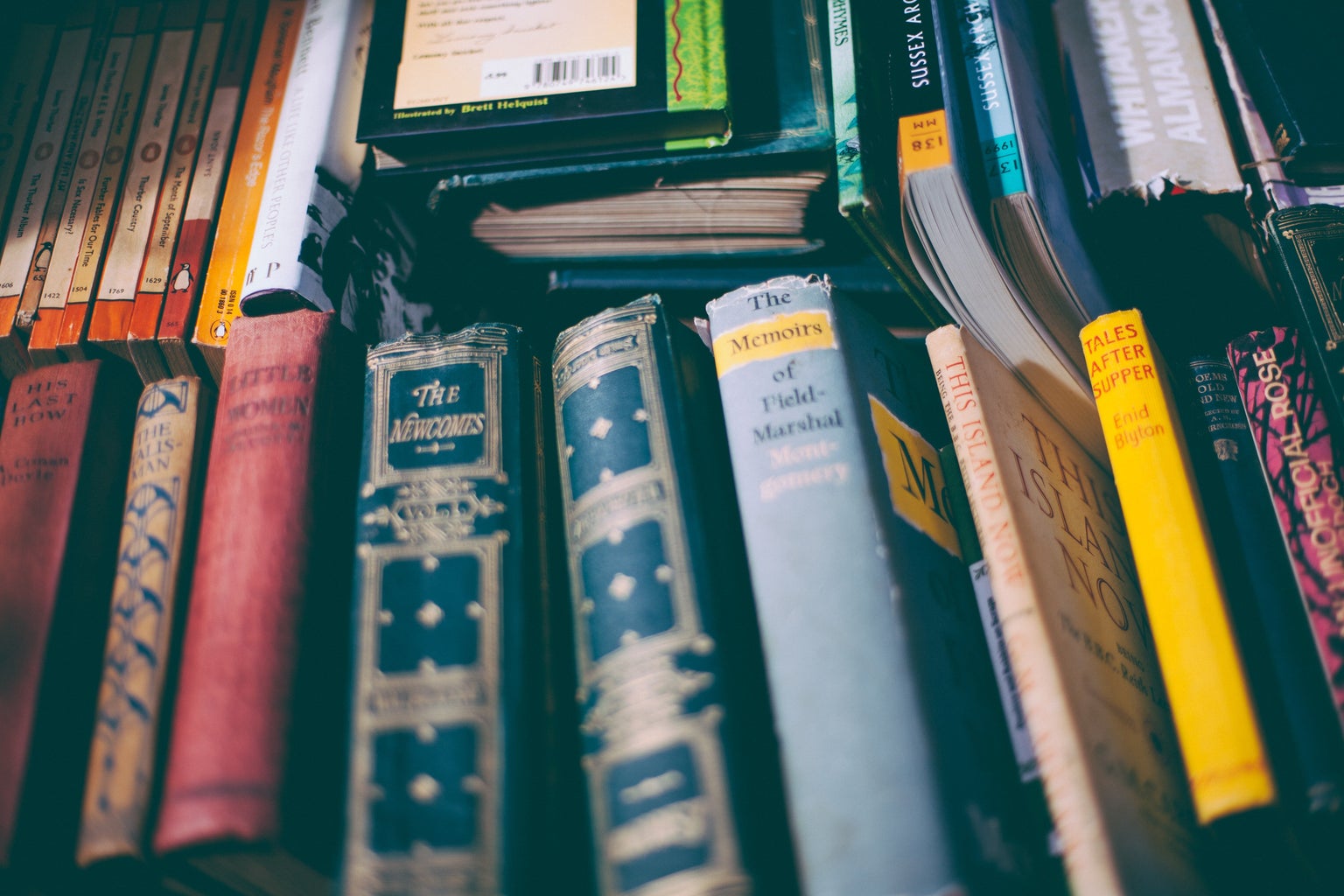

Mansfield Park by Jane Austen

People that know me might think I’m being predictable with this first pick because I talk about Jane Austen all the time, but I promise I have something new to say! I’ve read Mansfield Park close to five times now, and it wasn’t until a few months ago that I realized it can be read through the lens of chronic illness.

The novel, published in 1814, follows the poor and timid Fanny Price as she is adopted by her wealthy relatives, the Bertrams, and moved to their estate, Mansfield Park. It is a traditional Austen novel in the sense that the discussion of societal norms and relationship dynamics outshine any real plot, but it is also an outlier in several ways. Austen boldly addresses themes and topics in Mansfield Park that are not seen elsewhere in her work. Fanny Price is unlike any other of her heroines—she is submissive and sickly. I have always felt a particular kinship to Fanny, and I now wonder if it’s because she can be read as chronically ill. Often, throughout the novel, she cannot do everything that others her age can do and they remark on it. They call her weak or easily fatigued when she can’t walk as far as the others or gets a headache from working in the garden only a short time.

What I find fascinating is that Austen depicts Fanny in this manner, but never projects authorial judgment. Fanny is as she is, and Austen demarcates morally good and bad people by how they treat her. Austen never asks Fanny to become physically stronger, only mentally stronger, as a means to protect herself against those who don’t treat her kindly. This is only one of the many reasons why you should give Mansfield Park a chance.

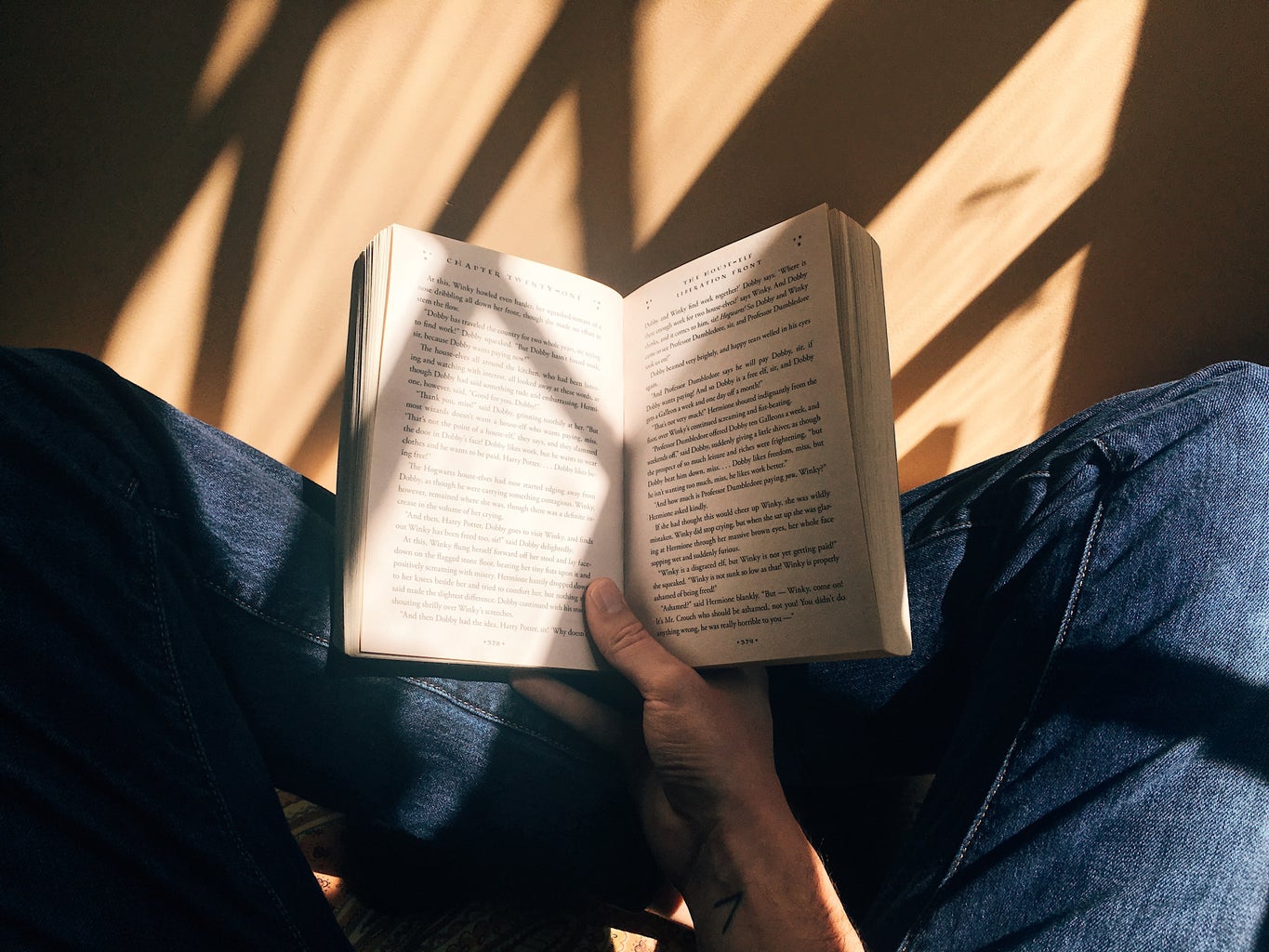

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

This novel was released last year to incredible reviews. People love this book and, though I didn’t adore every part of it, I think it’s one of the most comprehensive portrayals of chronic pain. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is about two friends, Sadie and Sam, who meet in a hospital when they’re kids and we follow their relationship for the next twenty-ish years as they become famous video game designers. Sam is originally in the hospital because he gets in a terrible car crash, leaving his foot in tatters. His pain and medical trauma underlie the entire story, shaping who he is and how he functions in the world. This is one of the most poignant quotes about his pain: “Weak, frail, alone, exhausted. He was tired of his body, of his unreliable foot, which couldn’t even handle the slightest expression of joy. He was tired of having to move so carefully, of having to be so careful” (117-118).

What I particularly love about Zevin’s depiction of Sam’s disability is how it dictates his entire life and the reader feels that almost as much as he does. The reader is never allowed to forget that Sam is in pain. His only reprieve comes from video games, where he can dissolve into another world. He explains once, “’Sometimes, I would be in so much pain. The only thing that kept me from wanting to die was the fact that I could leave my body and be in a body that worked perfectly for a while’” (70).

Tomorrow is quite a depressing story (for several reasons), but it is also riddled with hope. I believe the most profound example of hope is Sam’s chronic pain because he lives, succeeds, and eventually thrives despite it all.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence

I feel I ought to preface this pick. It might seem out of left field because Lady Chatterley’s Lover is infamous for its apparent approval of infidelity and scandalous descriptions of sex. A dramatically censored version of the novel was first published in 1928, but the story as Lawrence originally intended didn’t see the light of day until 1960. Lawrence lost friends, money, and status by publishing Lady Chatterley, eventually leading to a very public obscenity trial. This hullabaloo detracts from the deeper themes present in the story, like the repercussions of Industrialization, the importance of reconnecting the mind and body, and the healing power of nature.

I firmly believe Lady Chatterley has something to offer readers suffering from pain or illness. Lawrence lived the majority of his life in illness and eventually died from it in 1930 at age 44. His career was most active during WWI when he involved himself in politics, traveled the world with his partner, and published various short stories, poetry collections, and novels. Everyone came to a halt when he fell severely ill with tuberculosis around 1916, which remained untreated until his death. Knowing what I now know about Lawrence’s life, Lady Chatterley‘s overarching theme of being free in your body is less about scandalizing sex and more about valuing your body for everything it is capable of.

This story is first and foremost about Connie, a young headstrong woman, who marries Sir Clifford Chatterley, moves to his massive estate in the English Midlands, and must take care of him when he returns from war partially paralyzed. Connie, now Lady Chatterley, begins to resent Clifford for making her too feel paralyzed in her actions, thoughts, and behaviors. She stumbles upon love elsewhere with the groundskeeper of the estate, Oliver Mellors. They are crazy about each other and, through Oliver, Connie reconnects with her body and learns it holds as much power as her mind. She even explicitly states this in what I find to be an incredibly powerful quote: “‘Give me the body. I believe the life of the body is a greater reality than the life of the mind: when the body is really awakened to life. But so many people…have only got minds tacked on to their physical corpses'” (282).

The intimacy described and language used in this novel are no longer shocking to modern readers, and I wish more people would give it a chance. I cannot help but think D.H. Lawrence partly wrote Lady Chatterley’s Lover as a celebration of physical health, youth, and ability. Connie is full of life, but is suffocated by her husband and his insistence on intellectualizing the world—she finds a reprieve in Oliver, in the natural, common world he lives in. Sir Clifford’s poor health stands in direct opposition to Connie, yet it is never rebuffed or scorned. The war disabled him; Lawrence emphasizes that and takes a strong anti-war stance. There is so much to mine from this story and its depictions of pain, both physical and mental.

All’s Well by Mona Awad

My last recommendation is very intentional about its discussion of chronic pain. All’s Well centers on Miranda, a drama professor in her mid-30s who suffers from extreme pain after a bad fall some years ago. She hates her job, is at the will of her broken body, and feels like she has nothing to live for…Until she forces her students to perform her favorite play, All’s Well That Ends Well by Shakespeare. The plot of this one is hard to nail down, but a golden elixir, three mysteriously faceless men, and a slow descent into madness are involved. The novel is grounded in reality—in Miranda’s pain that never ceases and only seems to get worse—yet her journey to healing takes a magical turn. I found it to be a beautiful way to explain the feelings and sufferings that often seem unexplainable to those dealing with chronic illness or pain. Some of my favorite specifics are how Miranda obsesses over those around her who move effortlessly and how Awad toys with the idea of “performing wellness.”

All’s Well was released in 2021, and I hope it and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow point to a positive trend that more novels about those dealing with chronic illness and pain are to come. It’s comforting to hear stories about others that are facing what you’re facing, while also being engulfed in a fictional world. All’s Well takes you on that journey. At one point, Miranda has an out-of-body experience and reflects on it, reminding herself, “I’m in my body, which is my body. Breathing my own breath with my own lungs…Just my own pain. Familiar aches. Familiar concrete limbs. Familiar fists already tightening. It’s bearable for the moment. At least it’s just mine” (109).

We all only get one body and everyone’s operates a little differently. I’m learning to protect the one that’s all mine.