Fundamentalism is a mistaken theory of language: It assumes that every word of a text, whether sacred or secular, must be read as a statement of literal truth or a proclamation of the unshakable beliefs of the author. It is deaf to irony, metaphor, satire, allegory, provocation, ambiguity and contrariness. Writers seem to be especially vulnerable in polarized times when beliefs harden into dogma and those who hold opposing views are demonized.

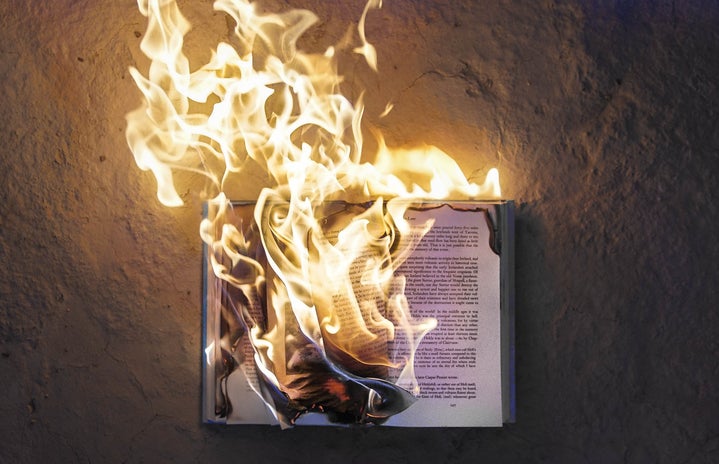

The attack on writer Salman Rushdie shocked the literary and art worlds. It was not only an attack on him but also on his creative imagination. The brutal and inhuman assassination attempt was also an indictment of those who continue to live in fear. However, books and ideas survive and continue to resonate, making it difficult to eradicate those ideologies and thoughts.

Rushdie’s novel features beautiful descriptions of angels and devils, as well as highly imaginative dream scenarios and marvellous provocations and revelations. It celebrates diversity while giving a satirical narrative of Prophets and politicians, as well as the British empire, hierarchy, dictatorship and cruelty. It is a work of magical realism that should be read whimsically and playfully and not literally.

Religious and political fundamentalists, on the other hand, have no intention of engaging in play, questioning, doubt or curiosity. In one passage in the book “Satanic Verses,” Rushdie gave a narrative based on ancient texts depicting the Prophet Muhammad being spoken to by the devil rather than God, which enraged the Islam fundamentalists. Similarly, Hugo Bettauer’s satirical book “The City Without Jews: The Day After Tomorrow” was written as a thought experiment to make readers consider the Jewish contribution to Viennese life, rather than inciting some bizarre violence.

On 7th January 2015, four of France’s most highly regarded cartoonists were among the 12 people murdered in an attack on the Paris office of the magazine Charlie Hebdo. The attack is considered retaliation for the magazine’s satirical portrayals of the Muslim Prophet Mohammed, an issue that has previously provoked many people before.

We think of the human body as fragile, but in many ways, it is more resilient than the environment that allows for vigorous debate, community discussions, and public readings. Assaults on French cartoonists, Rushdie and other artists around the world not only injured or killed them but also dealt a severe blow to such free expression. While the limbs and organs heal, public spaces are frequently shattered.

Of course, artists have had to deal with violence for millennia. History demonstrates through time that as soon as we were able to express ourselves, we were determined to eliminate anyone who offended us. Freedom of expression is a relatively new idea and it has always been delicate and incomplete.