My 13th birthday party was a chaotic flurry of DIY-ing, cupcakes, and music—all One Direction themed to prepare for their upcoming concert my friends and I had tickets to. We made tie-dyed One Direction T-shirts, sang along to all of their songs, and feasted on “I Love 1D” cupcakes, along with other junk food.

Looking back on my 13th birthday, all I feel is nostalgia for how carefree I was and my love for the people I spent it with. Although it’s only been seven years, which is a relatively short amount of time, the changes in attitude, feelings, and relationships all seem so extreme. So extreme that it doesn’t make sense to me when older adults refer to “their teenage years” as a jumbled yet homologous experience. My 13-year-old self was incredibly different from my 14-year-old self, who was different from my 15-year-old self, and so on.

Because my teenage experience seems so incredibly fractured, and because I’m about to turn 20, I’ve been reflecting on what “the teenage years” really mean. More specifically, what being a teenager identifying as female really means. What is a teenage girl to society? To her family? To herself?

To me, being a teenage girl didn’t really mean anything. It’s just who I am. Or who I was, by the time this article gets published. But I do think there is something about female teenagedom that is special.

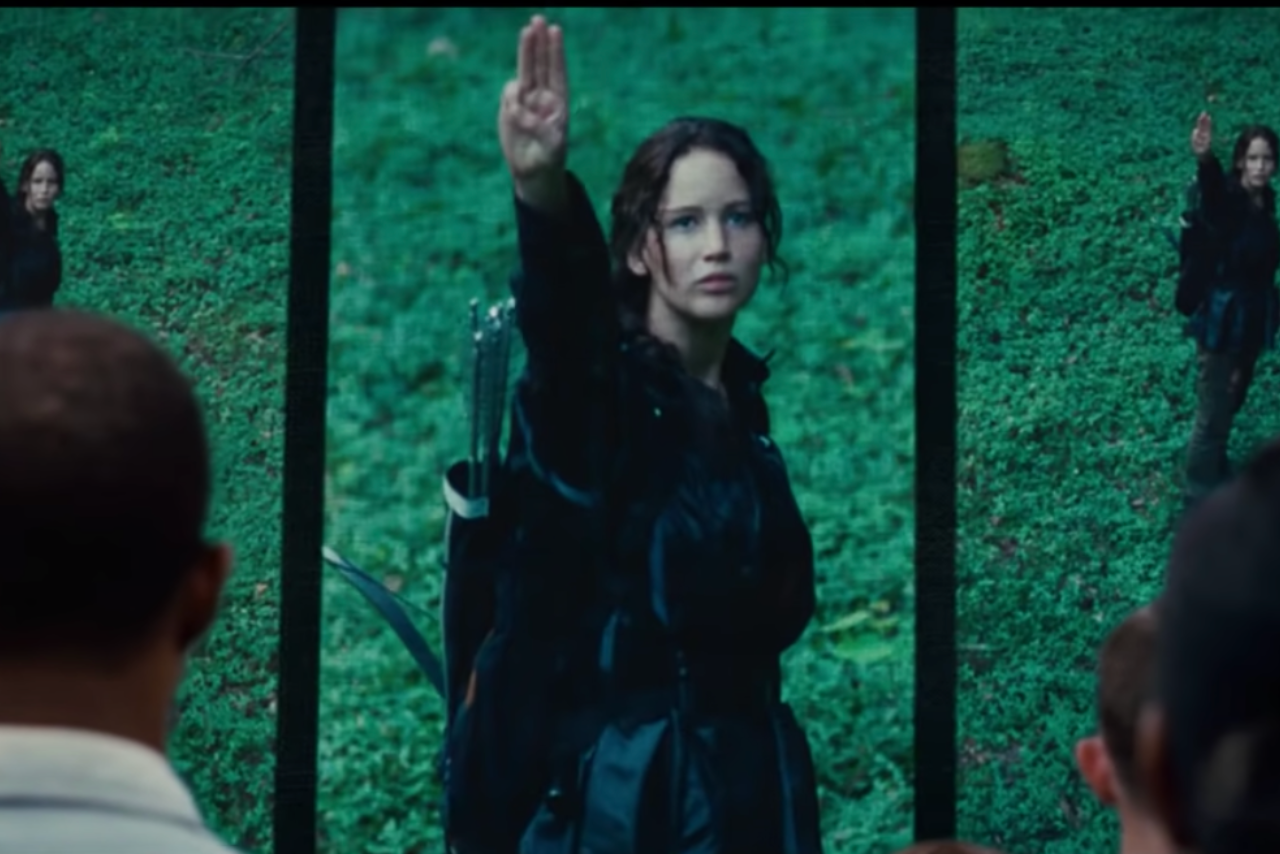

Female-identifying teenagers drive popular culture and the economy that revolves around it. The Hunger Games. Twilight. Harry Styles. Taylor Swift. These franchises all owe their start to us, and although immensely popular, they receive criticism often and are brushed off as “just for teenage girls”.

A classic example of how powerful my demographic can be is The Beatles. Constance Grady from “Vox” says it best:

“Teenage girls looked at that pack of floppy-haired Brits crooning in perfect harmony about hand-holding and holding on tight, and they thought, yes. They screamed and wept and pulled at their hair and fainted, because the band was perfect, the most perfect thing they’d ever seen, and they were overcome by the perfection…The Beatles went on to become one of the most influential rock bands in history, and the girls who loved them first were treated as the punchline of a tired joke.”

I’ve compared Beatles fans to One Direction fans (myself included—as shown by my 13th birthday party) multiple times in conversations with men. When I bring it up, I get laughed at initially, and then they get offended, angry, and defensive when they realize I’m not joking. One Direction is a recent phenomenon, relatively young in American pop culture. They’re still associated with teenage girls. The Beatles have been claimed by many men as the best band to ever exist. And, to these men, that means that teenage girls simply couldn’t be the first fans of the Beatles. Heaven forbid something we like is actually substantial. Heaven forbid a man reaps the benefits of pop culture that teenage girls built without immediately turning around and knocking those girls down once they claim territory.

This goes beyond music and movies, too. To be a teenage girl is to be seen as, like, unintelligent when using, like, slang that has been, like, so ingrained in English vernacular that like everyone uses it at this point. I’ve watched a friend argue about the application of the 14th amendment and how it has influenced the evolution of the Supreme Court while on a constitutional debate team (which is wholly impressive at the age of 16) only to be told she said “like” too many times in her argument for anyone to take her seriously. Is it because of “like,” or is it because teenage girls’ interests and actions are never taken seriously?

There is no winning as a teenage girl when it comes to her interests, her language, or her actions. Doesn’t like football? Typical female. If she loves sports? She’s trying to impress a guy, or she is a lesbian (which, for some reason, is still used as an insult). If she follows clothing trends? No personality. If she doesn’t follow clothing trends at all? Trying too hard. Is she a boy band fan? Mindless follower. Does she like indie music? Once again, trying too hard. Any interest a teenage girl has, can and will get made fun of.

I knew all of this already. I’ve spent seven years learning it. But what I haven’t realized until now, in my last year as a teenager, is that this dismissal of teenage girls cuts deep. If you’re not taken seriously, you’re an easy target.

To be a teenage girl is to get catcalled before you’ve gotten your first period.

To be a teenage girl is to have body image issues practically forced on you by all corners of society, and then get told that it’s okay that you’re insecure because “all girls are insecure about something”. As if that’s some sort of consolation.

To be a teenage girl is to see and shudder at the statistics that show that while women are often attracted to men their own age, men remain most attracted to teenage girls until death.

To be a teenage girl is to be told “it’s not you, it’s the grown men that might be around you” when not allowed by parents to go hang out with friends, or go to the mall, a park, a party, anywhere.

It’s dangerous to be a teenage girl. Girls aged 16-19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault. Yet when a girl makes a TikTok about being scared to go on walks alone, teenage boys will comment “don’t worry, no one wants you anyway” or “we’re good, thanks” (yes, I’ve seen this) because it can be a joke to them. For them, it’s not real life.

I’m not here to do a sociological analysis on sexism in my society or a scathing report on the impacts of uneducated male-identifying teenagers (although I could), but I think it’s important that while I’m a teenage girl, I take what I’ve learned about what it means to not be taken seriously and use it for some positive. I can be more empathetic towards others. As a cis-gendered white teenage girl, I can understand that you can be oppressed and be the oppressor at the same time. I can understand that life-or-death issues to one demographic can be played off as a joke to another. I think this makes teenage girls strong.

I also think teenage girls are strong because, despite the crap reputation pushed on all of us, we eventually learn that we don’t have to give a sh*t about what other people think about us.

To be a teenage girl is to dance with your friends to 2000s throwbacks without a care in the world.

To be a teenage girl is to get *that* feeling when speeding down the highway with the windows down on the first warm day after winter.

To be a teenage girl is to feel happy all day after another teenage girl compliments your shoes randomly on the street.

To be a teenage girl is to give away tampons to those who need them as if they’re free.

When I turn 20, even though I lose the label, I will still remember what I’ve learned in these past seven years. I still think being a teenage girl is just… who I am. Or was. Every person who’s gone through it knows that to be a teenage girl is just to be human. The rest of the world might, hopefully, eventually, learn that too.