Edited by: Aneesha Chandra

Trigger warning: bigotry, sexism, racism, ableism, homophobia, Islamophobia

Who is a good person?

Is it the happy-go-lucky store owner at the corner of your street who’s always selling appropriately-priced goods and positive vibes? Is it that exhausted working parent at a 24/7 convenience store, buying the chocolate they’d promised their kid at the end of a long day? Is it that Starbucks employee sitting next to you on your commute complimenting your makeup –“sooo on point!”? Is it the old man embracing his grandson when he came out as trans? Is it that budding model who cut their hair in solidarity when their brother lost all his hair to cancer?

Now, what if I tell you that happy-go-lucky store owner you see daily never sells to Muslims? What if I tell you that the overworked parent at the convenience store promoted sloppy-worker-Paul to Senior Manager over high-achieving-Lucy because Lucy is a woman? What if I tell you that the Starbucks employee gets a kick out of acting like they don’t understand their customers’ broken English? What if I tell you that the old grandfather hits his wife every other day when he’s drunk? What if I tell you that the budding model refused to give up their seat on the bus to a disabled person?

Are they bad people now?

We often forget that people are complex and multi-faceted. In a fast-paced world, we frequently attempt to confine people into certain pre-existing categories. We’re constantly using these unconscious mental heuristics to guess at the unknown as quickly and efficiently as possible without much effort. This is where the problem arises though; these “useful” shortcuts usually carry harmful stereotypes and lead to behaviors of racism, sexism, and homophobia, to name a few. These manifestations reduce people to one label or category — the color of their skin, their gender, their sexual orientation — and refuse to acknowledge the complexities that make an individual.

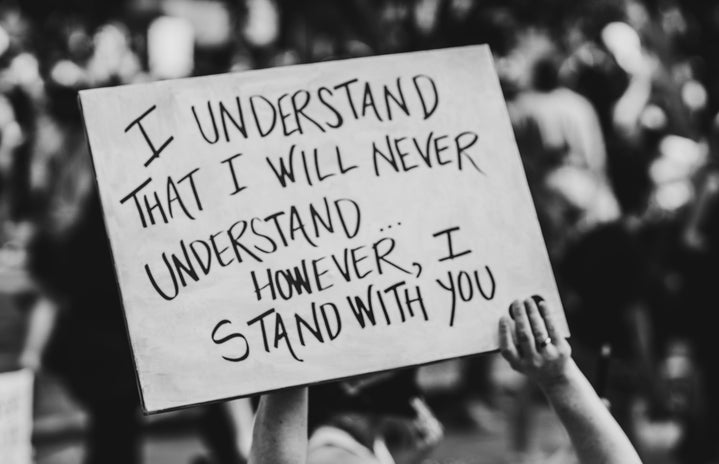

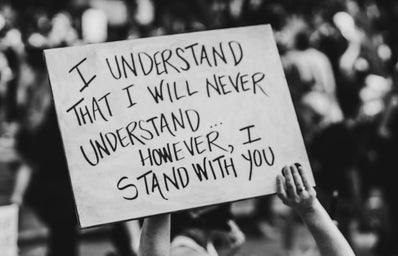

With the ever-growing number of voices calling for accountability and taking responsibility for one’s mistakes, one would have to be a fool to not reflect on their behavior and be mindful of their unconscious biases. We’re human though, prone to acting on unconscious biases. We make mistakes and will continue to do so in the future. Grappling with that idea is terrifying, especially in this time of exacerbated perfectionism and toxic cancel culture. The fact remains that we often stumble in life and break skin and bones. The scary part here is that sometimes, we’re not the only ones with a bleeding knee or a broken nose. Sometimes, the red-hot iron of our mistakes brands an innocent person more than it marks us.

Know that who you are as a person is defined not by your mistakes but by how you move on from them. Trying to always avoid mistakes is a perfectionist ideal that is impossible to live up to. It leads to isolating shame and guilt that is not only mentally exhausting but also ultimately shifts the focus to how bad you’re feeling rather than to the act of holding yourself accountable. This is not to say that you shouldn’t feel guilty. Feeling guilty may be seen as a sign that you care. Consider this, though: wouldn’t it be more worthwhile to funnel that guilt into taking responsibility and checking your biases in a healthy manner instead of obsessing over it, leaving it to rot, and then doing nothing about it?

Moreover, where is this guilt coming from? What is fuelling it? Not all feelings of guilt have good origins. It’s possible that your guilt has nothing to do with how much you care and everything to do with the fear of ostracization. It’s similar to how huge multinational corporations post the LGTBQ+ flag on their social media during Pride Month — for partial fear of being “canceled”. Is this short-term endorsement of Pride Month for fear of ostracization the kind of social justice we’re fighting for? Can we ignore the intentions if both the means and the end were good, especially when these are the same organizations that (not-so) secretly donate to politicians with anti-LGBTQ+ stances? Even if we did ignore the intentions, how long would we celebrate that “glorious” end?

More often than not, feeling guilty for slipping up could arise from both a sense of responsibility as well as the fear of being canceled. Navigating that space and reflecting on your intentions is tricky. However, do remember that our intentions are as intricate as we are. It may be difficult to untangle them. So, don’t give up. Keep going. Lean into your sense of accountability and attune yourself to it. Read, learn, and familiarize yourself with social justice movements. Mind your own business. Acknowledge your mistakes. Ironically, the best way to make fewer mistakes is to make a lot of mistakes. You’ll be a better person for it.