I’ll never forget the name Susan B. Anthony, who became a civil right’s activist and pioneer of the women’s suffrage movement after being denied the chance to speak at a temperance convention. The name was constantly drilled into my memory by my teachers for her contributions to women. But, as a brown femme, should I thank her for helping me get the right to vote?

Explicitly racist, Anthony didn’t care about people of color, only herself and other white women. It was Anthony who said, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.” Her beliefs failed to include intersectional feminism, yet she’s heralded every March as a feminist icon.

During Women’s History Month, this act isn’t something that should be praised. Many women didn’t get the right to vote with the 19th Amendment alongside white women. Native Americans, like Zitkála-Šáhad, had to advocate for themselves. Immigrant women had to wait until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 to vote. It wasn’t until the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that Black women were finally allowed to vote. Women of color have always been a part of women’s history, but it’s only white women’s often exclusionary contributions that get remembered.

Women of color have always been a part of women’s history, but it’s white women’s often exclusionary contributions that get remembered.

Let’s consider iconic feminist books in the public consciousness. The depiction and seduction of madness in The Bell Jar illustrates what it often feels like to be a woman. I enjoyed reading Sylvia Plath’s work as much as any other (hot) sad, literary girl, but Plath’s work is very white. In The Bell Jar, the main character uses different ethnicities to describe things as ugly and assaults a Black man. And while Plath was mentally ill, that doesn’t excuse the fact that her version of feminism is limited to “white feminism.”

Another “classic” feminist literary text is The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. It’s a gripping speculative tale of a dystopian United States with complete control of women’s reproductive systems, subjecting select women to constant rape in order to maintain a steady population. The protagonist of the story is white, but white women are not the ones most likely to be subjected to the state. Women from structurally less powerful communities — namely, BIPOC, low-income, and queer women — are more likely to experience state-sanctioned violence: For example, Black women are three times more likely than white women to experience force or the threat of force during a police-initiated stop, according to a 2019 report by the Prison Policy Initiative.

Sexual slavery and enforced surrogacy are not new to BIPOC communities. Who is and isn’t allowed to have children has been a matter of public policy since the U.S.’s beginnings. During chattel slavery, the law created complicated precedents that withheld the enslaved’s ability to consent yet enabled their ability to commit crimes. The Indian Adoption Project lawfully stole indigenous children from their homes and placed them in religious institutions or they fostered out to white families. LGBTQ+ folks may have their body regulated through conversion therapy, which are practices made with the damaging promise to change their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Heteronormativity can maintain a “desirable” population growth. During the 20th century, eugenics programs in the U.S. sterilized over 60,000 “unfit” people who were targeted for their mentally ill, disabled, Latina, and working-class social identities. Even now, recent immigrants revealed that they underwent invasive gynecology procedures, like hysterectomies, when they were detained by ICE.

Throughout history, white women have been viewed as delicate and innocent, using their femininity to weaponize racial anxiety.

Atwood herself said, “There’s a precedent in real life for everything in the book,” yet largely fails to consider or emphasize how race and sexual orientation create extra burdens for people with multiple marginalized identities. This can be, unfortunately, par for the course for a lot of feminist media and discourse.

Throughout history, white women have been portrayed as delicate and innocent, using their femininity to weaponize racial anxiety. Ava DuVernay’s 2016 documentary, 13th outlines how this portrayal became so ingrained into our society. During the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, white women created the narrative of dark-skinned people as sexual predators. This was upheld by cultural touchstones like the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, which portrayed Black people as threats to white women. The persisting myth enables white terror against Black men, and contributes to the Black community’s entangled, brutal history with the police.

This narrative also uniquely affects Black women: Professor of Law Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality,” to describe the phenomenon in employee discrimination affecting Black women. Distinct from white women, and distinct from Black men, Black women experience a hybrid set of challenges due to their gender and their race. Intersectionality allows a person to view societal oppression through more than one lens.

Decolonize your celebration to include local community organizers, your friends, family, and ancestors.

White feminism’s failure to take these multiple lenses into account is why feminism often gets a bad rap. How is this liberatory? Feminism should be about coalition-building across social identities. No matter how well-meaning, the exclusivity of white feminism and trans-exclusionary radical feminism (like J.K. Rowling invalidating transgender identities) are antithetical to the more Gen Z and BIPOC-accepted “intersectional feminism.”

Intersectionality is the reason why Women’s History Month needs to encompass more than the experience of upper middle class white women — their racial, sexual, and other identities inform their experiences as women, and celebrating women’s history means considering all women’s history.

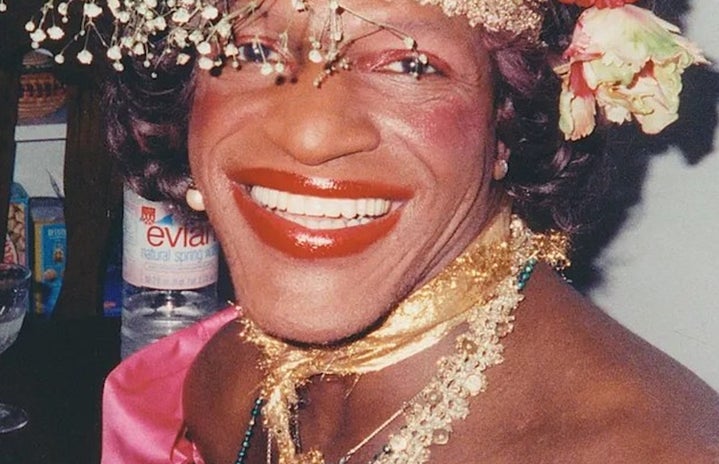

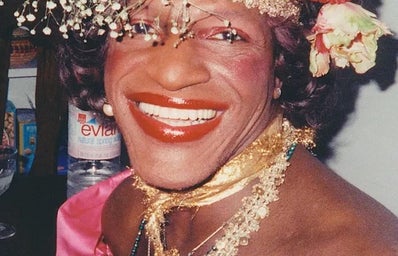

Marsha P. Johnson is often uplifted during Pride Month, but she should be praised during Women’s History Month as well. She brought gender to the forefront of LGBTQ+ discussions during the Stonewall Riots and the rise of the Gay Liberation Front. Johnson was cognizant of transgender people’s increased likelihood to be homeless and targeted by the police. Despite her hyper-targeted identity, Johnson continued to protest and be outspoken, inspiring others to continue the resistance movement and fight for their rights.

The list goes on, with more women with various abilities, backgrounds, orientations, shapes and sizes, educational attainment, socioeconomic statuses, nationalities, and identities. So, this Women’s History Month, decolonize your celebration to include local community organizers, your friends, family, and ancestors.

Centering white women narrows the scope of women’s gains and our potential for more change.

If you want to read a non white-centric iconic feminist work, check out Toni Morrison to start. The Bluest Eye explores Black girl childhood and internalized racism. Her magnum opus, Beloved, constructs a narrative for someone who didn’t have a voice — in other words, an untold history. There’s too many unheard WOC stories drowned out by the white-centric mainstream.

Additionally, celebrate the ongoing historical achievements of women from marginalized communities. Sandra Oh was the first Asian woman to have hosted a major awards show and win multiple Golden Globes. The Harvard Law Review elected its first Latina president, Priscila E. Coronado. A lot more has been accomplished, and a lot more needs to be done. Undocumented residents still can’t vote, but you can bet that non-citizens are still politically engaged — they are organizing to get their voices heard another way. Undocumented activists can volunteer to gather signatures for ballot initiatives, plan and attend marches, share resources, provide webinars, talk to their voting eligible network, and publish writings on their experiences to advocate on their own behalf.

Centering white women narrows the scope of women’s gains and our potential for more change. Include Black women, Brown women, queer women, trans women, disabled and neurodivergent women, and all women in the celebration of Women’s History Month to avoid catering to white supremacy.