Marketing these films shouldn’t be hard—and yet big studios fall flat every time.

A select few in this world have been chosen for a destiny not many will fulfill, not because of their lack of luck, but quite the opposite: possessing the luck that saves them from having a history in youth theatre. Those destined for drama have learned a couple of things in these school productions: stand on the X, project your voice, and the fact that “all celebrities are ex-theatre kids.”

We know better than anyone that film and theatrics go hand-in-hand, and you can’t have one without the other. Even so, there’s the existence of films that have recently premiered and attempted to hide their roots in song and dance: Mean Girls, Wonka, and The Color Purple, to name a few. But why hide such a vital part of your movie? The answer is simple: the world hates theatre kids. Whether or not the world is just in this belief is neither here nor there, though, it is something that film marketing teams have noticed. As these melodic movies roll out, the solution to this odd obstacle seems clear: market your film to those who would want to watch it, and understand why they are interested.

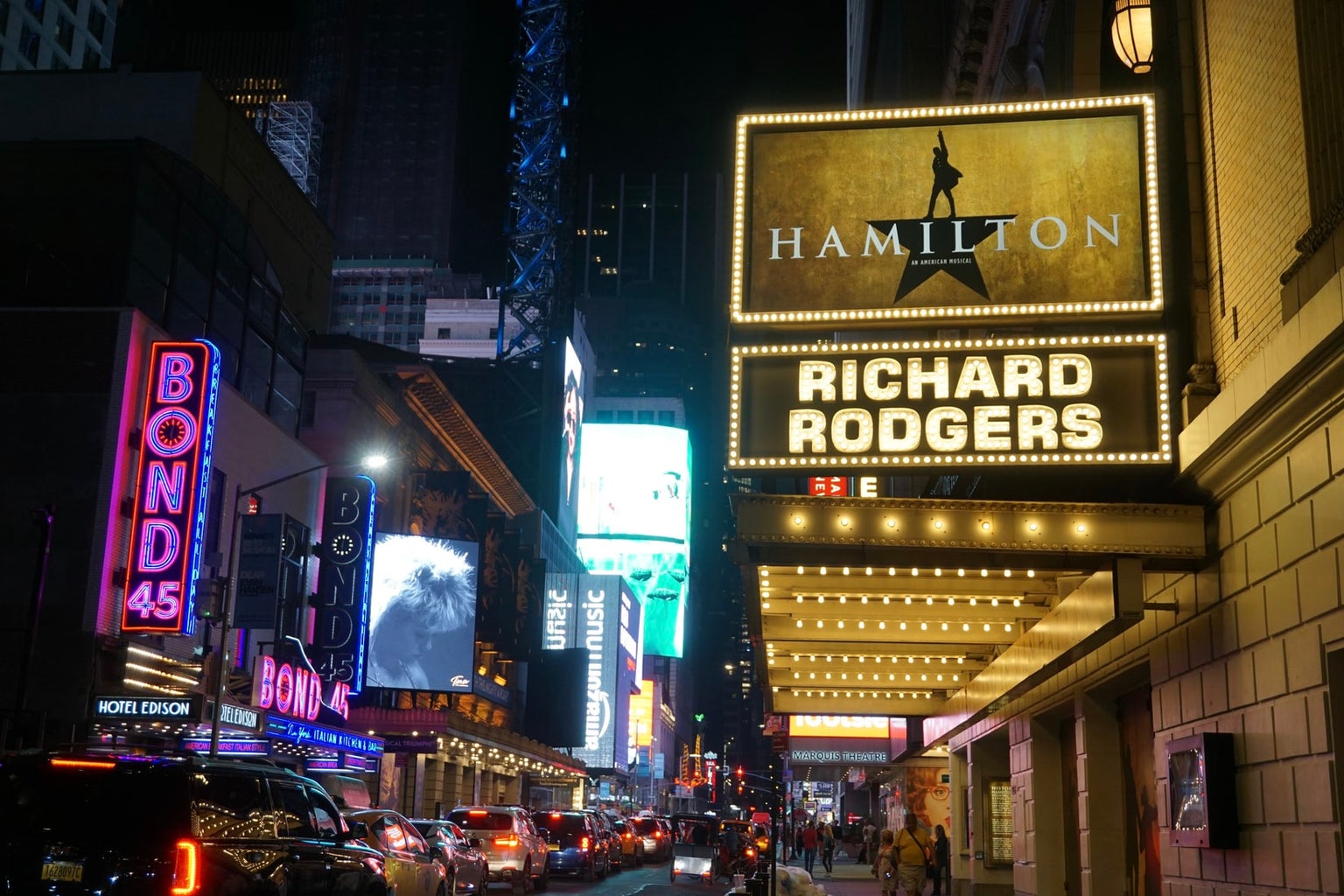

Avid musical fans, reluctantly known as theatre kids, know that there is an audience who gawks over the spectacle only a Broadway show can bring. Movie adaptations attempt to charm people as their predecessors once did but fall flat when bringing in a new following. In turn, this betrays their ardent audience. When basing films on popular Broadway pieces, who do studios think made these productions so popular?

Let’s be honest: musical fanbases are typically fueled by high-schoolers who want a song to add to their repertoire in preparation for Seussical auditions. Films of this nature should pull from the melodrama of their groundwork. Audiences flock to hear songs they’ll love, but the visual complement is what makes them memorable. Does it matter if the audience likes a song if they won’t even remember it after leaving the theater? Going “full-musical” isn’t just beneficial, it’s necessary. If critics of movie musicals consistently slam the notion of “randomly breaking into song and dance,” why make it random?

Performance in a musical should be expected. Studios should be plastering these songs over trailers and posters, and yet, these numbers are usually lucky to have a nod in “Teaser Number 2.” We love musicals because of the extravaganza that catchy songs and visual companions bring.

Disparagers of this genre will never like movie musicals. Whether their reasoning is their stubborn attitude or the music itself, this isn’t something that marketing can fix, although they’ve tried. Being tricked into watching a musical film will only fuel their flames of hatred, not fan them out. Those who love movie musicals do so because we love movies and musicals, and this simple breakdown is taken for granted. We must embrace spectacle, display melodrama, and parade performances—the right audience is waiting for it.