If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably found yourself scrolling through BookTok, a niche subgenre of TikTok where users discuss books, authors promote their work and readers leave reviews of the latest off their TBR (To Be Read).

In the age where a single Instagram story or Vogue article will reveal that the Hadid sisters are obsessed with The Outsider, or that Harry Styles swears by My Policeman, it can be hard to figure out what exactly to read and what books to spend money on in a sea of options. Young readers, who don’t have a disposable income to spend on books or reliable transportation to public libraries, can be especially confused. Here’s where BookTok comes in.

BookTok has not only made reading trendier but it’s also condensed recommendations into a neat algorithm formulated specifically for each user. Sure, you may want something with romance, but what about something with romance and horror and magic? Recommendation: The Diviners by Libba Bray. As you consume more and more content centered around your favorite genres and sub-genres, your FYP (For You Page) becomes increasingly tailored to your likes and dislikes. You can also find yourself in unique reader spaces, such as those for people who love books revolving around LGBTQ+ characters, or those who want to read more by Black or Asian authors.

There are many advantages to BookTok’s methodological approach to pushing books (besides being recommended exactly what you want to read when you want to read it), like Barnes and Noble stores across the country staying open when they would have closed otherwise. An announcement that many stores would be closing by 2022 has become basically defunct as a result of BookTok and the growing popularity of reading, an almost miracle save considering the record low sales the famous bookstore had been facing before COVID and prior to the emergence of BookTok according to Bloomberg News. Now, B&N even has its own BookTok List.

It’s not just readers that can’t get enough of BookTok— established authors (like Madeline Miller, author of The Song of Achilles), have seen their works become popular again, to the point where they hit the top of the New York Times Bestsellers list nearly a decade after they were first published. The same rings especially true for new authors, too. Writers, especially those who are in their late teens or early twenties hoping to make it big, are given a platform to market their own books. One such self-publisher, Olivie Blake, author of The Atlas Six, used marketing techniques like relaying short snippets of scenes and making edits of her characters and artwork to help get her previously self-published book popular enough to be offered a deal with a traditional publishing house. Other smaller authors have been able to cultivate a following through BookTok by using popular audios and hashtags to attract readers’ attention. Now, it seems, almost anyone can make it big in the publishing industry, with the only requirement being to market yourself well enough to make connections with readers and other popular published authors.

But the chance to make it big applies to every book, not necessarily well-written books. Sure, smaller authors can be offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but what happens when the books they market aren’t ready to be published? Many editors complain that younger authors who lack the experience of their older counterparts shouldn’t be published— in their words, they’re not good enough writers yet, and constructing a plot, complex characters, and building an entire fantasy world is no easy feat. But BookTok pushes young writers to publish before they’re ready. After all, Chloe Gong was published as a college student and her book became a bestseller, so why can’t mine?

The truth is that the publishing industry is a lucrative business, and what sells and doesn’t sell isn’t so easy to predict. Publishing houses will pick up already popular books on BookTok because it makes their job easier. They won’t need to spend the time, money, or manpower on promoting books they sign deals with because everything is already done for them. This causes books that aren’t well-edited to be picked up just because they already have a following. The reality is that many agents and traditional firms ignore smaller authors who can’t or won’t self-market their books on all the social media platforms they have, though their books might objectively be better written.

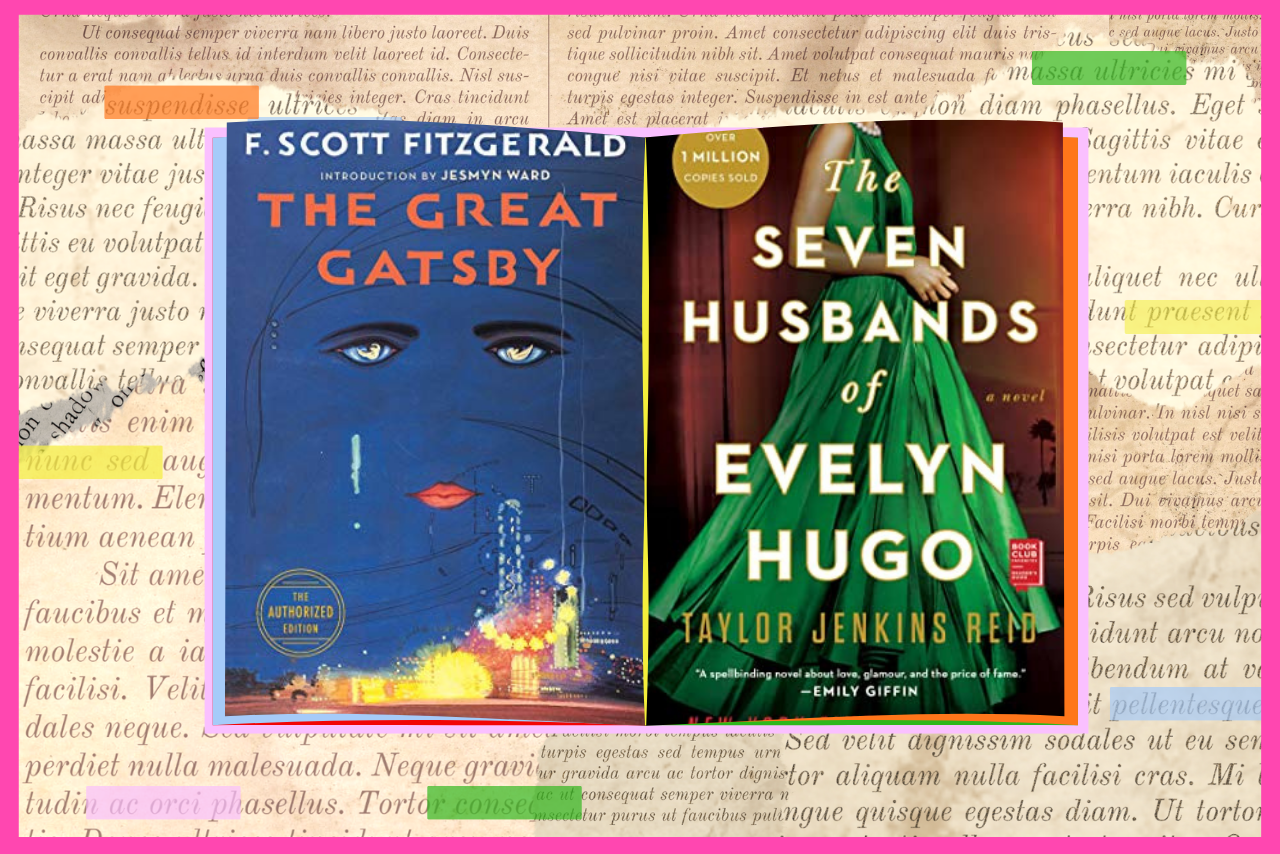

When this happens, the publishing industry becomes rife with an overwhelming number of books, all similar genres, all neglecting greater themes of love, loss, or morality in exchange for the same generic tropes. It’s well-known that books that make the rounds on BookTok feature romance, a fan favorite amongst young-adult and new-adult readers, but often these books are all mostly the same. When all you see recommended as enemies-to-lovers is The Shadows Between Us and A Court of Thorns and Roses, or Red, White and Royal Blue as queer romance, BookTok becomes just a cycle of the same ten books, featured in TikToks over and over again.

What if you’re looking for a unique concept? Well, books that don’t feature or advertise common romantic tropes don’t become as popular as books that do. This forces authors to include formulaic tropes in their stories out of a desire to be published, regardless of whether these scenes benefit their plot in any meaningful way.

They’re called tropes and clichés for a reason. Clichés are repetitive and unoriginal by nature, but we love reading them because, if written right, they can be genuinely funny or romantic. When written poorly, however…well, the recent controversy concerning Lightlark, written by twenty-something-year-old Alex Aster, is a good example of BookTok hype gone wrong. Aster became famous on BookTok after she began marketing her second novel, Lightlark, about a deadly magic competition. She grabbed the attention of hundreds of thousands of BookTok users by advertising tropes featured in her book, such as enemies-to-lovers scenes with “knife to throat,” “forced proximity” and sexual scenes she called “spicy.” Her dedicated followers even rated the book five stars on Goodreads months before it was set to be released, resulting in such an unprecedented increase in popularity that Aster revealed her cover on Times Square, with a reaction-TikTok she made eventually garnering more than 250,000 likes.

Just a few weeks later, Aster announced a seven-figure movie deal, bought by Universal Pictures before the book was even out. Flash forward to after ARC’s (Advanced Reader Copy) of the book were sent out, and the scandal erupted. Whole scenes, sentences and tropes that Aster said were supposed to be in the book weren’t found, and the scenes that were there weren’t well-edited. Many complained that the book was deceiving and offensive in its unoriginality, leading some to cancel Aster by review-bombing Lightlark one star on Goodreads, blasting her online on all her platforms, and calling her “an industry plant.” Any mistake, however small, can cause angry readers to lash out, targeting an author before really understanding the situation or context of their novel and perpetuating cancel culture.

So how exactly is BookTok saving the publishing industry? By making reading just as trendy as crocheting or thrifting. BookTok has achieved what major publishing houses haven’t been able to do in years: keeping bookstores alive, making reading popular, marketing up-and-coming authors, and selling large volumes of books, some of which aren’t even new releases.

As we know, for every advantage BookTok has given the publishing industry, there are just as many negatives. With its “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” mentality on tropes and clichés, rampant pushing of marketable authors, and recommending the same genres over and over again, the platform has proven to be a very decisive means to an end.

But at the end of the day, what more can we expect out of TikTok?