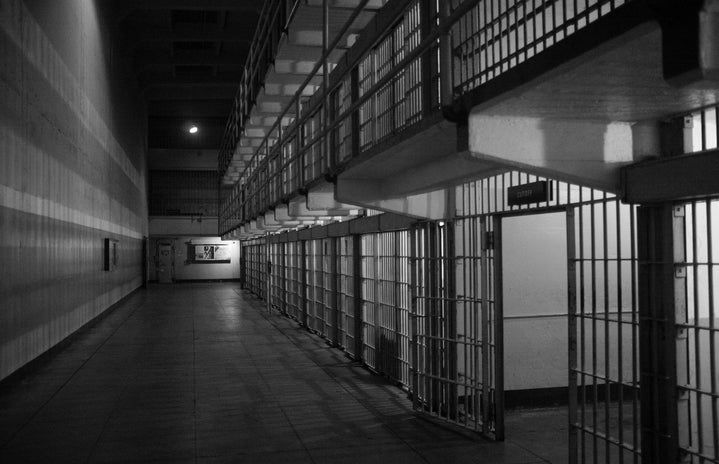

My first time visiting San Francisco was in the fall of 2014. At the time, the only perception I had of the Bay Area were its excursionist sights—the enthralling, congested Lombard Street; the photogenic Golden Gate Bridge; and, of course, the freakishly famed Alcatraz Island. Although I only ever saw the latter from a Pier 39 vantage point, I recall how isolated the outlying Alcatraz island seemed. Even then, eeriness settled into my body as I observed the flocks of people waiting to board the cruise ships that took turns visiting the infamous prison.

Before the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary opened in 1934, there were its many predecessors. Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia took the spot for the first American jail in 1773, which then expanded in 1790 as a means of emphasizing prisoner reform through reflection, penitence, and thus rehabilitation through good conduct. This reflected the Quaker ideology of inhabiting a monastic, sequestered space in order to repent for one’s sins.

In 1829, the Eastern State Penitentiary became the first “modern” prison. Here, the early principles of rehabilitation and restoration continued to take the shape of solitary confinement at a larger scale, in which prisoners were locked in singular cells and prohibited from all forms of social interaction. The prison continued to expand to keep pace with the influx of prisoners, going from three cell blocks to fifteen by its closure. On its creation, architect John Haviland aspired for the gothic-like fortress to “strike fear into the hearts of those who thought of committing a crime.” Between overcrowding—ironically enough—and corrupt guards, the claim of rehabilitation became completely warped.

Now, after hundreds of years and in the age of mass incarceration, Eastern State Penitentiary has been transformed into a place of dark tourism. After closing in 1971, it was converted into a historic site where visitors can experience “a Halloween festival of epic proportions,” as the penitentiary’s website promotes during the holiday season. It is not the only of its kind, but it certainly takes the cake in terms of magnitude and ambition. The website has a “shop” section in which visitors can sift through prison-inspired souvenirs, from shot glasses to a “bestselling” t-shirt inscribed with the penitentiary’s name. The website also boasts that 300 prisons were “inspired” by the penitentiary. Its influence and magnitude are further evident in the fact that in its earliest years of operation, Eastern State Penitentiary attracted some 10,000 visitors.

I don’t contest the idea of acknowledging and thinking heavily about criminal justice ideologies by seeing these sites in person, but the potent commodification, enchantment, and false attraction of such a violent and dehumanizing system rattles my bones. During my 11 a.m. political literature lecture, Professor Poulomi Saha further unveiled the uncanny essence of the Eastern State Penitentiary’s annual haunted house. She described the terror that the entire scene manufactures, not in terms of ghosts or jump scares like that of conventional haunted houses during the spooky season, but rather in its architecture, violence, and history. She explained that twistedly enough, people like to frequent such attractions simply because they are marketed and perceived to be innocuously fun—a falsity that should be extinguished in the age of mass incarceration.

Considering numerous policies like mandatory minimums and “three strikes” laws that have contributed to such an inhumane crisis, prison tourism, which is seemingly “fun” and innocent, is another factor that anesthetizes visitors to the brutal cycle. From the very establishment of the prison system, inmates have been made spectacles, constantly watched and monitored. Now, with forms of entertainment like prison haunted houses, the very structures that housed cases of intense dehumanization have become a display as well. By commodifying sites that have “inspired” the further creation of prisons where reports of poor, detestable living conditions, brutality, and forced labor have occurred—and been legalized—popular culture is normalizing something that is obscenely abnormal.

The highly successful marketing of prisons as just another pop-culture commodity is startling.

Alcatraz hosts over 1.5 million paying visitors annually, making it one of America’s top tourist attractions, while Eastern State Penitentiary gets around 250,000 paying visitors annually.

Concurrently, there are over two million incarcerated people in America. The United States makes up almost 5% of the world’s population, while simultaneously accounting for 20% of the world’s prison population. When people tour prisons in lighthearted nature, it is important that they recognize the intense disgrace that the commodification of these structures can have on currently incarcerated people, who are essentially “slaves of the state” in relation to the 13th Amendment criminal-exception loophole.

The sites, which are grotesque and perverse in nature, have become compensatory places that are aestheticized to meet society’s entertainment needs. By making it seem that people can gain insight into the world of former prisoners through dark tourism, non-prisoners are only made more distant and desensitized towards mass incarceration. Things like prison haunted houses make non-prisoners believe that what occurs in prisons is essentially mythological and does not affect them.

It’s important to remember that the antithesis of criminalization is humanization, not commodification.

Mass incarceration has an atrocious domino effect that, in most cases, prison tourism can subsequently downplay. Contesting things like prison-inspired shot glasses and themed haunted houses are steps to be taken to show that imprisonment is not some inevitable normalcy. While the consumption of these commodities is only a culmination of a state-produced crisis, public consciousness is necessary for counteracting commercialized prison culture. So while the Eastern State Penitentiary celebrates 15 “attractions” filled with terror and entertainment, it’s important to remember that the antithesis of criminalization is humanization, not commodification.