No one has been on a tour de force of new fiction quite like Sally Rooney. Her books appear on best-seller lists, the “New & Noteworthy” sections of bookstores and (perhaps more personal to me) on Instagram explore pages (placed aesthetically beside lattes and plants). Rooney’s rise to literary fame is fascinating considering the subject matter of her work; books about twenty-something year-olds with chaotic sex lives that break out into rants about Marxism and Brexit are on the same lists as run-of-the-mill Romance and Fantasy books, or captivating biographies about Donald Trump. In a world that has become increasingly didactic and formulaic, where a piece of art is either problematic or woke and nothing in between, it is refreshing to see critics and consumers alike embrace the nuanced character studies of Rooney’s texts that are hard to define moralistically.

I read my first Rooney book, Conversations with Friends, back in 2019. Taking my initial glance at the book’s pages, I noticed there were no quotation marks around the dialogue. Upon actually reading the novel about university friends Frances and Bobbi becoming involved in a pseudo-romantic dynamic with an older couple, photographer Melissa and actor Nick, I began to interpret the choice of no quotation marks as not an unnecessary confusion but as an intentional yet subtle formal choice. As Rooney’s characters all simultaneously hurt and flirt with one another as affairs and lies run amid, subverting the punctuation typical of a novel seems to demonstrate the lack of difference between these characters at-large. Despite their quirks –– Nick is a C-list actor with golden-boy looks and Frances is an esoteric Trinity College student who dabbles in writing –– they all face the ubiquitous battles of desiring to be loved and maintaining a worthwhile career. Rooney invokes her decision to collectivize her characters when she told the New York Times “I don’t really believe in the idea of the individual […] I find myself consistently drawn to writing about intimacy, and the way we construct one another.”

The solidarity between all of Rooney’s characters so far, spanning her three published novels, and their similar emotional struggles reflect Rooney’s politics that are interspersed in dialogue. Rooney exhibits an acute awareness of the privilege of her characters that attend prestigious Irish universities like Trinity College, and this awareness is ever so heightened by the author’s own Marxist inclinations. Confessing my left-wing sentiments here, I usually am in agreement and quite fascinated by the political tangents of her characters and how they intersect with their relationships at large. Normal People, Rooney’s sophomore release and arguably her most famous novel, deals with class in an especially interesting light. The male love interest of the book, Connell, comes from a working-class background whose athleticism makes him popular in high school, but fails to obtain this same social status in the university. Long gone are the days of being the fastest one on the soccer team in hopes of guaranteeing you the largest friend group and now, at Trinity College in Dublin, what makes you noteworthy is how much Jacques Derrida or Jacques Lacan you’ve read. In a slightly metafictional passage, Rooney outlines achieving social stardom through intellectual ramblings as students “come into college every day to have heated debates about books they have not read” and that it is “culture as class performance, literature fetishized for its ability to take educated people on false emotional journeys” (Rooney, Normal People). Her latter take is especially blunt in considering Rooney is most likely attune to how her audience is likewise “educated people,” upper-middle-class Millennials and elder Gen Zs attending post-secondary institutions. Rooney’s hyperawareness does not only make for more smart and complicated character studies, but allows the reader, in turn, to reflect on how they consume literature.

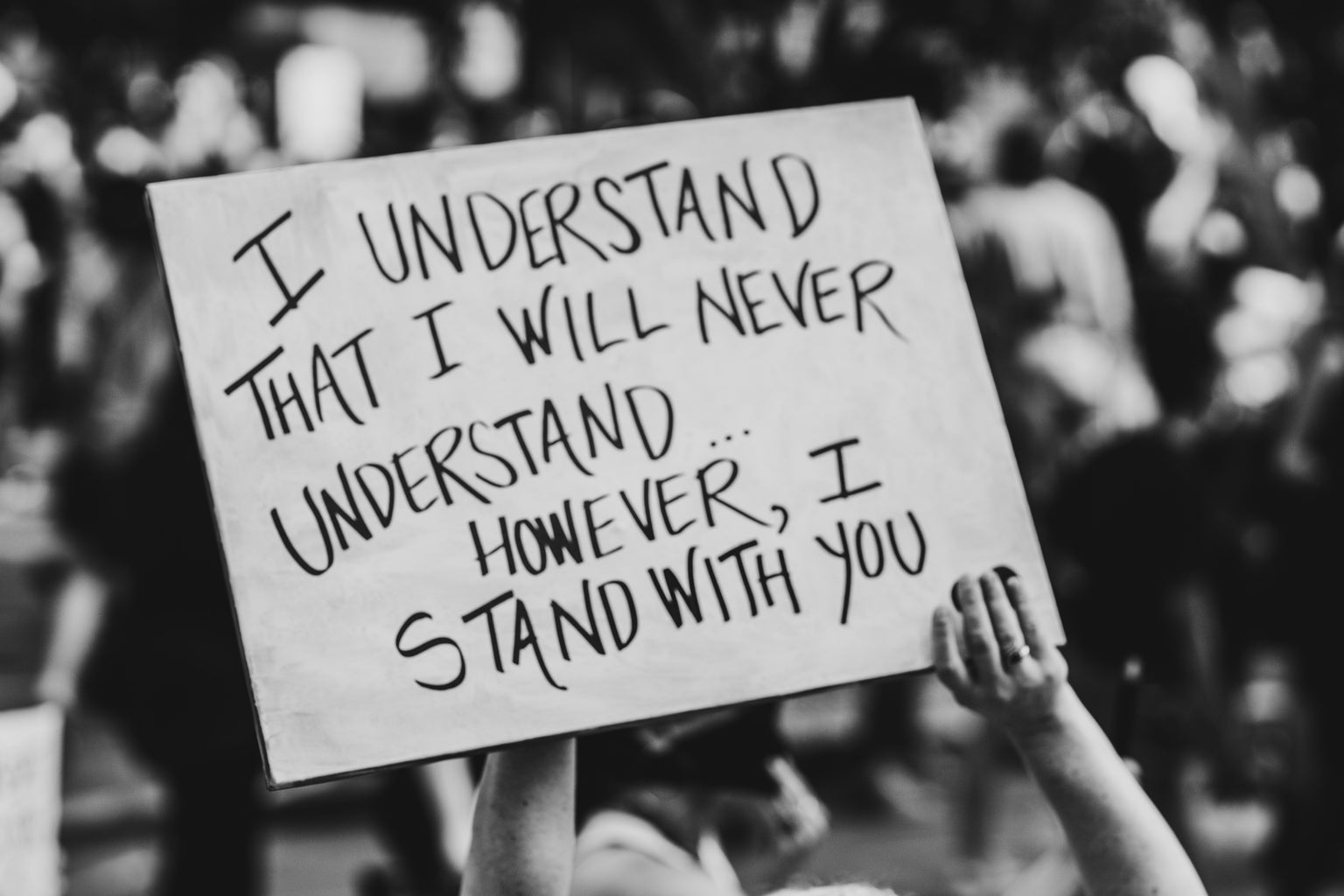

Her latest release Beautiful World, Where Are You is the culmination of Rooney’s subtle psychological insights and left-wing ideology, but there is an intervention to this common narrative mode in that Rooney’s new novel likewise speaks back to much of the criticism that she has received. Ironically, the stimulus for Sally Rooney hatred is the same reason why she has amassed a cult of readers: her characters are repetitive, indecisive and go on spontaneous political rants that often do not move the plot forward. Rooney has been accused of being one of the “educated people” she often attacks, and people believe her work to be hypocritical. These contradictions, however, are not proof of Rooney’s ignorance and cognitive dissonance but instead are testimony to the fact that despite the Communist Manifesto(s) that we read, we are all inevitably still within a capitalist society, to which we live in and love in. Rooney writes, in the perspective of character Eileen writing to her friend Alice, “what if the meaning of life on earth is not eternal progress toward some unspecified goal […] the meaning of life remains the same — just to live and be with other people” (Rooney, Beautiful World, Where Are You, 161). While we debate and ponder big solutions to big questions through navigating political theory, we often forsake localizing our existences to those we love. Not to encourage turning a blind eye to current events and pressing matters of the external world, but as Rooney’s characters converse about how to make the economy fairer they can’t even call their significant other “boyfriend” or “girlfriend.” This seems especially representative of the modern generation: there was a tweet circulating, during the George Floyd protests, that Gen Z will punch a cop but not be able to make themselves a doctor appointment. While this was very much hyperbolic, I think there is something true about the sentiment that we have become estranged and unable to engage in basic human interactions, yet believe we have the power to end police brutality for once and for all. Rooney’s work comments on this behaviour, and advocates not only for trying to strike a balance between the personal and political, but taking it easy on ourselves if we struggle to do so.

What I admire most about Rooney’s novels is that despite the sometimes scathing portrayals of the human condition, she emphasizes the importance of love, intimacy and relationships regardless of our faults. While she does not hesitate to craft characters who make mistakes and are unlikeable at times, Rooney is not a nihilist and, above all, sees the good in people. A line from Beautiful World, Where Are You that encapsulates this notion is when Alice reflects “I was sitting half-asleep in the back of a taxi, remembering strangely that wherever I go, you are with me, and so is he, and that as long as you both live in the world will be beautiful to me” (Rooney 164-165). There is something both profound and simple in expressing gratitude towards the ones we love, and that they make our world better. It is important to note that Alice writes this to Eileen; many chapters of Beautiful World, Where Are You are emails sent back and forth between the two. Rooney choosing to write this notion in dialogue, and not keep it as a private thought of one character, ironically allows for the isolated act of reading to remind us that, in Rooney’s own words, we “construct one another,” whether through emailing, sex or debating about books we’ve never read at university.