Every once in a while, when I’m reading something for an English class, I’m suddenly reminded that people have always been… people. Centuries of time and huge cultural and scientific shifts between us, and yet when I read through a pamphlet war that took place between 1615 and 1620, all I could think was: Wow. Put this in modern English and it could be a Twitter battle in the 21st century.

Allow me to set the scene:

It’s 1615, and a fencing master named Joseph Swetnam is bored. What could be a better use of his time, he decides, than publishing a rant against women, under the (super subtle) name of Tom Tel-troth? (Seriously. “Swetnam”? “Tel-troth”? I wish I was making these up).

Enter his pamphlet: The Arraignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward and Unconstant Women: Or the Vanity of Them, Choose You Whether. His lovely rant includes such gems as “men will be persuaded by reason, but women must be answered with silence, for I know women will bark,” and “at the beginning… a woman was made to be a helper unto man, and so they are indeed: for she helps to spend and consume that which man painfully gets.” Translation: women are irrational and will spend all your money. In the rest of the pamphlet, he tells young men not to marry because women are angry and impossible to get along with, and “He that has a fair wife and a whetstone, everyone will be whetting thereon” — a bawdy joke that essentially means women will probably cheat on you if they’re pretty enough to get men’s attention. This guy. What a catch.

Swetnam admits elsewhere that he is not a scholar or a noble — his occupation is a fencing master. This shows in his writing: the pamphlet is full of words he’s incorrectly paraphrased from different authorities, confused Biblical and classical allusions, and terrible grammar. And that’s exactly what the women who responded to him seized on.

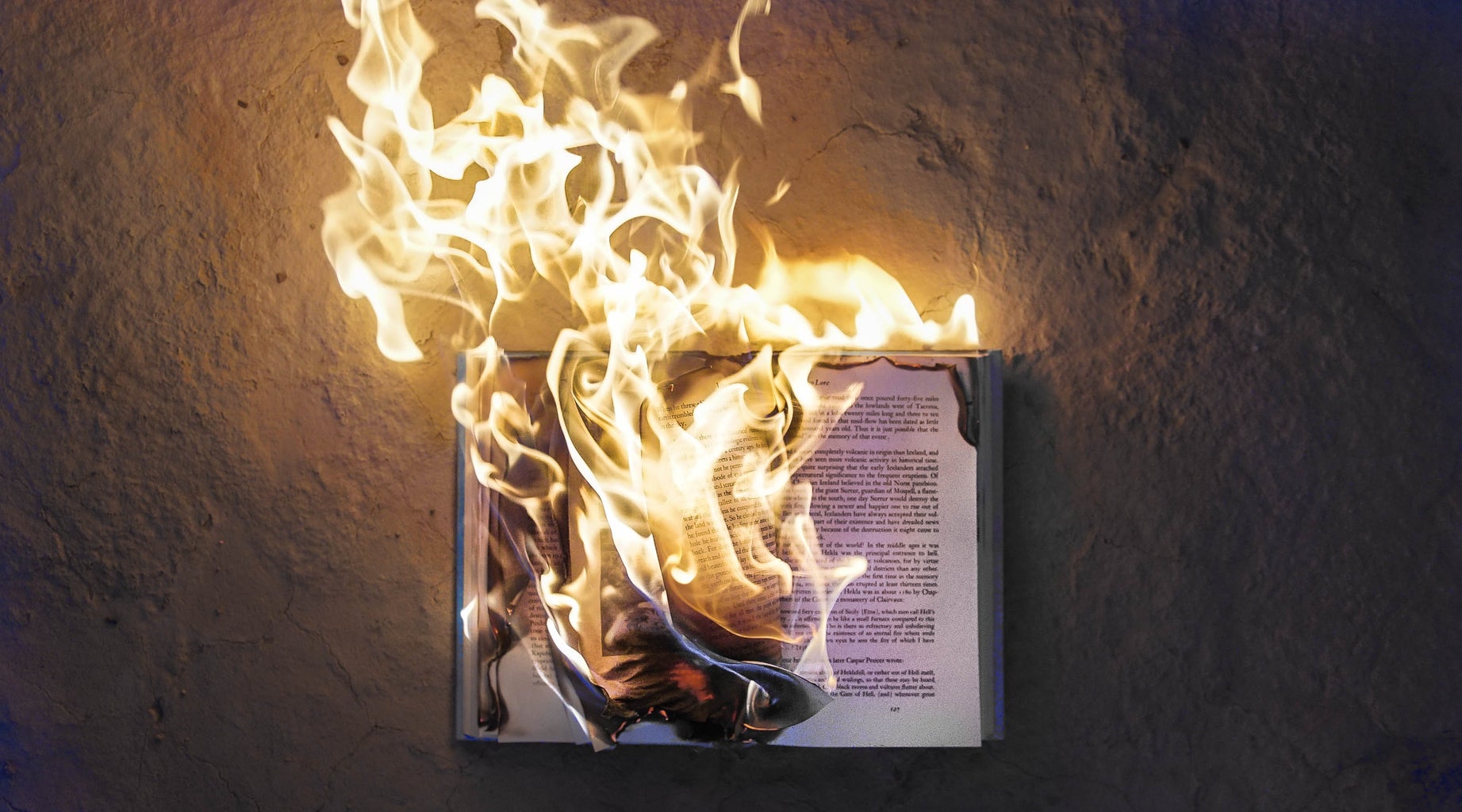

Because delightfully, all this came back to bite him. Although the pamphlet itself unfortunately garnered enough popularity for four reissues of his book, it also provoked several responses — especially from women, who did not like what he had to say.

19-year-old Rachel Speght was the first to publish a response to Swetnam in 1617, called A Muzzle for Melastomus — the title compares Swetnam to a dog she’d like to muzzle. Several others followed, but Speght’s response made her the first known woman to publish a feminist treatise in English under her own name. And it was in response to an anonymous man running his mouth in a public place. Somehow, that seems fitting.

In the style of the time-honoured tradition of exposing trolls on the Internet, Speght doesn’t honour Swetnam’s pseudonym for a second — she immediately calls him out by his real name in the introduction of her pamphlet. Here’s how she opens her response: “From standing water, which soon putrifies, can no good fish be expected, for it produceth no other creatures but those that are venoemous or noisome, as snakes, adders, and such like. Semblably, no better streame can we looke should issue from your idle corrupt braine.” In other words, she says his brain is like still water: it has no movement, so it putrifies and produces only venomous or annoying thoughts. What an elegant way to tell someone they’re an idiot.

She also calls out his bad writing, which is “without grammatical concordance” and a “promiscuous mingle mangle” as well as a “hodgepodge of heathenish sentences” (I may need to steal those!). Limited as she is by her age and gender in this period, she still writes a scathing retort to Swetnam, calling him out by name, critiquing his grammar, and using her education to show off her own intellect as she dismantles his speech.

In other words, Internet discourse (such as it is) was alive and well in the 1600s! People were exposing anonymous trolls and picking apart the weaknesses of their posts as soon as public discourse (on paper, instead of online) became a thing. There’s something comforting and funny about that — no matter what time or country we’re born in, sometimes we just like to be a little petty. If there’s one thing I’ve taken away from this, it’s that people are fundamentally people. We can be stupid, ignorant, wise, judgemental, smart, and — above all — hilariously consistent.