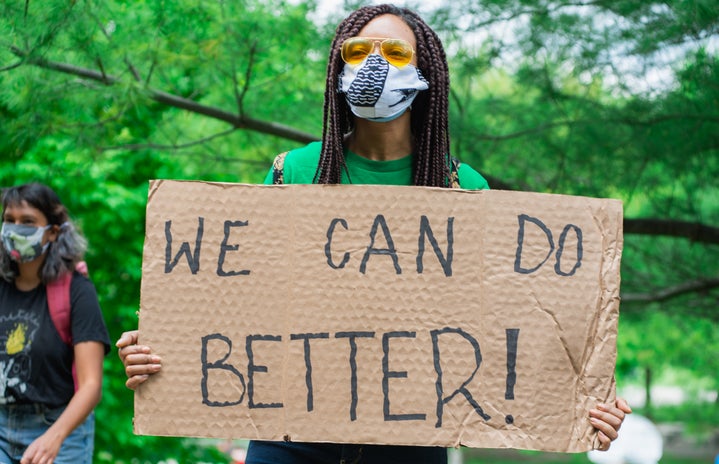

“We messed up.” “I’ve failed.” “We can do better.”

Over the past two months, it’s been common to see such messages in aesthetically pleasing Instagram posts from a myriad of brands and social media gurus who have been called out, cancelled, or disowned for racist behavior in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. Their millennial pink, minimalistic or bold typeface apology posts have been hitting Instagram feeds since the beginning of the protests.

What can be said about the Instagram Apology? How genuine is it if while promising to change their behavior they prioritized keeping the aesthetic of their feed? Is it appropriate for companies and influencers to approach apologizing this way, or does it open up a larger conversation about their need to maintain their normal Instagram feeds in the wake of a movement?

For Alyssa Coscarelli, more commonly known as @alyssainthecity, some of her 334,000 followers had mixed opinions on her insta-activism.

When the former Refinery29 writer began posting “action items” to her feed (a list of ways to participate in the Black Lives Matter movement with a corresponding days-of-the-week design) many accused her of performative activism and virtue signaling. Acquaintance Subrina Heyink came forward with her own experience with Coscarelli, where Coscarelli told one of her coworkers at Refinery29 that it’s “always something with” Heyink, a jab at Heyink’s passion to discuss Blackness and Black Lives Matter on her Instagram feed. In response to her past remark Coscarelli posted her aesthetically pleasing “Thursday Action Items for Black Lives Matter” post and then hid her apology behind that cover.

“As someone who works in social media, it’s painfully obvious that you are still trying everything you can to maintain you [sic] aesthetic, engagement, and brand, over pausing and showing humanity,” user @abbigaylem wrote in response.

Two days later, Coscarelli stopped posting her aesthetically-pleasing action items and finally typed out a straightforward apology about her comment on Heyink’s activism, about which she states: “No matter its intent or wording, was a form of racism.”

But Coscarelli is only one example of what seems like a plethora of cases. Jen Gotch, founder of Ban.do, has recently come under fire for multiple instances of racist behavior. Gabriella Sanchez, a former employee, explained through an instagram post that her time working at Ban.do was “plagued with racism and emotional manipulation.” Soon after Sanchez’s post, more employees, both past and present, came forward about Gotch’s behavior and what they experienced working for Ban.do.

Ban.do’s first response was an apology that aligned visually with their normal branding: millennial pink, their signature font, clean formatting. In scrolling through your instagram feed, you would assume it for just another regular post from the brand promoting events or a new product line; not the kind that makes you stop dead in your tracks to read further. In an interesting turn of events (the co-founder and CCO of Ban.do, Jen Gotch, resigned) the two subsequent posts slowly lost their color: first to gray, then to a stark white.

Reformation, the popular fashion brand that rose to popularity under the guise of environmentalism and sustainability, was not far behind Ban.do. Founder and CEO Yael Aflafo stepped down after employees leaked emails and Instagram posts that were filled with racist behavior. In response, Reformation posted a minimalist black tile in their signature font with the words: “I’ve failed.” Later, a statement about a commitment to change was draped against a video of a palm frond and running water, only for the account to be left unattended for over a month.

Dolls Kill, a company that prides itself on catering to people with a “rebellious attitude,” issued their own apology after co-founder Shoddy Lynn posted a photo to Instagram of cops in riot gear standing in front of a Dolls Kill storefront; the caption was “Direct Action in its glory. #blacklivesmatter” The Dolls Kill instagram page then posted an apology that uses early web and AIM slang (“We Hear U”) and continued back to its normal feed shortly after.

It should be noted that each company and influencer mentioned has continued to post statements since their initial apology, but when faced with callouts for toxic behaviors, it’s off-putting for brands to continue to market and sell an identity or a trademark. Social media, being as young as it is, can feel like the Wild West, and it’s true that it can be tricky to navigate. It’s messy and unforgiving. One thing, however, should remain clear: racist behavior should not be masked behind someone’s social media persona, and neither should the apology.

Hiding behind a brand offers the perpetrator a chance to detach themselves completely from the conversation. How many hands, one might wonder, do these apologies pass through before being posted? What were the choices behind a pink background, behind chatroom slang reminiscent of AIM and the early web? The layers between the perpetrator and the finished product pile high, but even behind a wall of boss babe marketing, racism, no matter how beautifully packaged, is still racism.