I know it’s hard to believe, but women get angry. Very angry. Extremely angry. Female rage has been taking over pop culture in the 2020s, and thank goodness it is. From the revival of admiration for 2009’s Jennifer’s Body to Olivia Rodrigo’s #1 hit “Good 4 U”, women are angry and not going to apologize for it. And frankly, I am all for it. And is it any wonder why? The women of 2022 have so much to be angry about. However, society views anger as a very un-feminine emotion, and emotion that women don’t possess, when really it’s the opposite. Women are angry. Not crazy. Not manic. Not sensitive or frustrated or dramatic or unreasonable. Angry!

Angry women have been explored in entertainment since Ancient Greece with plays like Medea and Lysistrata. While Jane Austen is the 1800s most prominent female writer, she didn’t often explore female rage. Marry Elizabeth Braddon’s 1862 novel Lady Audley’s Secret dealt with murder, insanity and female rage. In the 30s and 40s, the femme fatale archetype became immensely popular, with the archetype centering around women who used their sexuality and seductiveness to seek revenge on men with films like The Killers and Out of The Past being examples. The film Question of Silence has become a feminist classic despite sparking fierce debate upon its release due to it showing violent women. The once-feminist film Fatal Attraction has recently been re-reviewed as anti-feminist, due to its coining of the misogynistic term “bunny boiler,” which means “a woman who acts vengefully after having been spurring by her lover.” This term was also used in Pretty Little Liars by Alison when she and Aria destroy Bryon’s office. Similarly, once praised by feminist critics, Thelma and Louise, about two women who go on a Bonnie And Clyde-like journey after an attempted rape, has recently been branded as “toxic feminist.” And despite Sharon Stone’s character in Basic Instinct being named “one of the best female performances in screen history,” it has sparked backlash for stereotyping lesbians as vicious through protests from the LGBTQ+ community.

Now, many films throughout cinematic history portray toxic masculinity and male anger, with American Psycho and A Clockwork Orange being some of the biggest examples of showcasing male brutality. However, these action films and thrillers are also examples of how aggression is a perfectly okay male trait. These films are some of the highest-grossing films, with Indiana Jones and James Bond being full franchises, and often sidelining female characters.

In the last 30 years, female revenge movies have stemmed from the same understandable, but an unoriginal concept: a sexualized woman gets hyper-personalized revenge in response to rape, attempted rape or the loss of a child. Kill Bill is the perfect example of this as the antiheroine “The Bride” seeks payback against a group of assassins, but in the process, she kills her unborn child. This represents how our society only sees female rage as justifiable if they involve their children, due to the stereotyping of female emotion and purity.” The star-studded film Girl, Interrupted also showed young women’s anger against societal expectations and traditions, which was a welcomed refresh of the female rage genre during this time, as it was a group of women expressing a variety of rage, rather than a single woman angry at a man, or group of men.

The 60s and 70s show a movement of capitalizing on the sensationalizing the controversy of female brutality, making it the first time the topic was showcased widely on screen (and therefore making it representation for progress’ sake, but still not good representation). This would often be an exercise for gratuitous nudity and graphic violence because they were often shot from the male gaze, the perspective of a straight man. It’s also worth noting that this was during the sexual revolution, a type when sex and sexuality were becoming more normalized than ever before. Think about the rape-revenge flicks Ms .45 and Lipstick as examples. An exception to this is Rosemary’s Baby, which focuses more on feminine trauma then violence toward women, as its focus is more psychological then physical. While this was ahead of its time during its release in 1968, in hindsight, it’s nightmarish and not exactly empowering or validating.

The misrepresentation of violent women goes beyond just pure maltreatment and belittlement. It goes back to the Hays Code days of Old Hollywood, a strict list of rules for what could be shown in the movies at times from storylines and characters involving a race to sex to gender. It also goes back to society and women being lesser then. If you look throughout cinematic history, it’s very difficult to find a female fight scene before the 1980s, and even then, they are simple and restrained punches, slaps or pushes, when we all know women have a lot more anger than just a simple slap.

You also can’t talk about female rage without talking about women in horror movies. The first thing you probably think about when you think of women in horror flicks is the final girl trope. Coined by Carol Clover, describes it as the last woman standing in horror films, usually of the slasher variety. Think The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween and Scream. What originally started as a way to showcase strong, empowered women on screen, as they overcome such a traumatizing circumstance compared to their other, usually male, counterparts. However, in reality, it’s very stereotypical. Why? Because like everything surrounding women in media, it has to do with sex and sexuality. Her sexual friends are killed off one by one, while the final girl’s virginal status is rewarded with her sole survival, showing how virgins can still be empowered with them being allowed the final strike to the killer. This retroactively tells the viewer that being virginal is lifesaving when your sexuality has absolutely nothing to do with that. And it’s even more sexist when these virginal characters are often sexualized due to their direction being from the male gaze.

There are many examples of female rage throughout cinematic history that are from the male gaze. The film Teeth, which drew on the myth of vagina dentata AKA a vagina that has teeth, showcased a man’s fears about the female body and its unknown qualities, qualities that they have no interest in actually learning about. Female monsters like these are seen as freaks of nature, much like in the Scarlet Letter or its modern film adaptation of Easy A. In the landmark book The Monstrous-Feminine, Barabra dissects why female bodies have so many ties to the horror genre, as well as Erin Harrington, the author Women, Monstrosity and Horror Film. Sady Doyle’s explores why women are ostracized for daring to defy a man’s image of her in her book Trainwreck: The Women we Hate Mock and Fear.

The recent spike in female directors (something that is long overdue), female is something to be explored more in cinema, especially in the rape-revenge genre with Revenge, MFA, Promising Young Woman, Take Back The Night and Violation all telling rage-fueled stories of antiheroines from the understanding perspective of the female gaze. This fantasized retribution is hardly surprising in the post-#MeToo climate and in a world where Roe V. Wade doesn’t exist anymore. Feminine rage films like Black Swan and Promising Young Woman are also to prestigious films, as both received Oscars, proving that these kinds of themes and stories are appealing and captivating to audiences and creatives and are worth making in the first place. There’s also Silver Lining’s Playbook and Hereditary.

Last Night In Soho is another film from 2021 that deals with themes of female rage. However, this one is different from the rest because it was directed by a man, Edgar Wright, known for his smooth one shots and colorful cinematography. This is important because it shows that it’s not that men can’t create good female rage stories, it’s that most just frankly don’t want to. In contrast, the male rage film American Psycho was directed by a woman. Anya-Taylor Joy “has a thing about feminine rage” were it’s almost a through line between most of her projects, with Thoroughbred and her recent flick The Menu being examples.

Gone Girl and A Simple Favor are other female-revenge movies with female rage at the center. Amy Dunne’s cool girl monologue describes the frustrations of bland comments intended to be complimented, they quickly turn into sexist nicknames. Emily Nelson’s story begins as a conspiracy for money but quickly turns into revenge when her husband barely grieves her and ends up sleeping with her best friend. Both these women are hardly role models. But their actions are somehow justifiable despite their crooked moral compasses. Why? Because sometimes society’s pressures on women just get to me too much, and sometimes we have to let it all out.

Teen films often dissect the complexities of female rage and women in relation to the horror genre, but with the added intricacies of teenage struggles and hormonal frustration. Netflix’s The Babysitter, Barely Lethal and Violet & Daisy are examples of this. Another is the 2022 A24 film Bodies Bodies Bodies. The slasher-satire is set up as an “every woman for herself” tale of a group of teenage girls where a party turns into a fight to the death. Critics praised it for killing fo the men first and keeping their sexually active, messy, flawed, and juicy women alive, defying the virginal final girl trope. The thing is, is that feminine rage doesn’t just have to exist within the horror and thriller genres, it can exist in any genre, drama, coming-of-age, comedy, rom-com, animation. Anything! This makes sense because women don’t need to be traumatized to feel anger. they can feel angry about anything, just like men. Mean Girls is one of the most iconic coming-of-age comedies of the 21st century. It, of course, features the Plastics expressing their rage through the notorious Burn Book, as well as Regina George’s iconic minute-long scream. Now, granted this is a little bit toxic, but it is certainly refreshing and entertaining. The early 2000s indie flick Thirteen, which introduced Nikki Reed and Evan Rachel Wood, is another example of showing teenage feminine rage, with the film centering around teen rebellion, frustration and anger.

The 2009 film Jennifer’s Body is one of the most iconic teen female rage films. The film has become a pop culture phenomenon, with Halloween costumes, GIFs and outfit recreation all over social media and even music and music videos making references to the film. Originally a commercial failure due to a misleading and sexist marketing strategy centered around Megan Fox’s sex appeal, the film has seen a revival in recent years and has gained the moniker of being a cult classic. The film opens with Amanda Seyfried’s Needy saying “Hell is a teenage girl.” These 4 words encompass exactly what the film is about, and exactly why it has remained so culturally relevant. The Diablo Cody-written story is about the transition from a normal, gorgeous girl to a vengeful demonic woman. It centers around best friends Needy and Jennifer. Needy is dorky and more of a rule follower, while Jennifer is stunning, confident and sexually liberated. The setting is a town called Devil’s Kettle. One night, they go to see the rock band Low Shoulder’s concert, an emo band with a secret obsession with the occult. The band coaxes Jennifer into its tour van after the show. However, the band has ulterior motives for just hanging out with a pretty girl. They need her, who they think is a virgin, to be a sacrifice for Satan in exchange for fame and fortune. But Jennifer isn’t a virgin, so instead of dying during the ritual, she turns into a demon who needs to feed on boys to sustain herself. Jennifer is angry about what happened to her, making her have no remorse for her new destiny. If anything, she relishes in it. However, Needy slowly notices something is up, and her anger over her best friend’s transformation eventually reaches a boiling point.

Karen Kusama’s film has recently been evaluated from the feminist lens. While the critics viewed it from the (at the time) default straight male gaze, the film is actually a commentary on the death of innocence, sexuality and trauma, making the implications of the film disturbingly familiar in a post-#MeToo world. After all, the film starts going after a band basically gang-rapes a teenage girl for their own gain. Its a funny bonding event for them, nothing more or less. Essentially, Jennifer’s arc is a cathartic revenge fantasy, as she attempts to use her violated body to get vengeance on the patriarchy. This is why the studio’s marketing strategy surrounding Megan Fox’s sex symbol status was so distarous and misleading. Its not a sex fantasy, its a revenge fantasy. A fantasy ground in relatable rage and familiar toxicity. The female gaze this film was made from was ostracized, and ahead of its time. So, in a time when an audience is hungrier then ever for female stories, it’s no surprise this catastrophic failure is creating a new life.

Soraya Chemaly, author of Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger says that girls are conditioned not to recognize their own anger or focus on their own needs at all. This is because anger is stereotypically a masculine quality, not a feminine one. That’s why exploring the theme of female rage is so important. It shows women that its okay to be angry. It validates them. Teenage girls, especially, are basically pop culture’s punching bag. Look at Twilight, Gossip Girl and The O.C. These shows are targeted toward teenage girls, and yet their impact on pop culture is often sidelined with people preferring to ridicule these shows. However, projects like these are also cash cows for Hollywood, which makes their existence fairly simple; Hollywood will make them, but they won’t respect them or put effort into them. Another teen horror film that showcases this message of female anger, trauma validation and fantasizing about revenge is 1976’s Carrie, which is one of the most referenced horror films in media.

Olivia Rodrigo has become one of the biggest stars in young Hollywood since her debut single “Driver’s License.” Her album Sour is essentially a heartbreak album, but Rodrigo comes from a place of anger instead of heartbreak through songs like “Traitor,” “Brutal,” “Jealousy Jealousy,” and mostly “good 4 u,” which is only one out of two pop-punk songs on the ballad-heavy rage-fueled album with the other punk song, which is just as anger, being “Brutal.” The music and every performance she has done with the song all feature displays of feminine rage, possibly becoming the spark that created 2021’s “the feminine urge” meme. The rock anthem uses themes of sarcasm and retribution to showcase the character’s rage. The song has a distinctive 90s/2000s pop-rock sound in the same vein as Hole and Paramore, a fan has even created a mashup of “Misery Business” and “good 4 u.” Rodrigo also seemingly shouts her lyrics, further showing her rage.

In the video, Rodrigo plays a seeming normal teen girl. Like Jennifer Check, she’s on the cheer squad. However, her undoubtedly disinterested expression while practicing her cheer routine suggests that something is on her mind. The audience begins to catch glimpse of something more sinister underneath the surface, mirroring Jennifer’s Body with the viewer being Needy and Rodrigo being Jennifer. She bumps into her cheer mates, seemingly purproseful due to how she doesn’t apologize. She decorates her locker with an X’d out picture of a boy. She dons black latex opera gloves, giving an edgy dimension to her periwinkle cheerleading uniform. By the climax of the video, she applies makeup as if getting ready for a special occasion, only for the viewer to find out that the occasion is committing arson. By the final chorus, she is dancing manically in her ex-boyfriend’s bedroom which is covered in blazing flames. By the outro, she retreats to the woods and finds a pool of black-blue water. Her eyes are demonic red and her smile is devious and accomplished. She has gotten her revenge, and the liberation is palpable.

The music video for “good 4 u” is a stylistic, punk and youthful take on feminine rage with clear 90s and 2000s references. Directed by the popular creative Petra Collins, the video references both 1999’s Japanese horror flick Audition and Jennifer’s Body. In the behind-the-scenes video, Rodrigo talks about her and Collins are fascinated by female rage, and that they love expressing in creatively. She also mentioned how it since often a theme explored in media.

Jennifer’s Body’s soundtrack also featured many pop-punk songs from Black Kids, and Paramore, which are not only nod to the 2000s alternative scene, but also show how the soundtrack matches thematically to the film’s message of validating female rage. So, “good 4 u” referencing the film in a music video that deals with female rage, after all, Rodrigo’s character sweetly buys a gas canister and SmartFood popcorn on her way to torch her ex-boyfriend’s bedroom, shows how this theme of female rage is undeniably continuously relevant.

Another rageful song off of Sour is “Brutal,” which while “Good 4 u” is unhinged and unapologetic, it doesn’t exactly pass the Bechdel test, being that her anger is about an ex, even though the song can be interpreted in many ways (personally, my past experiences with awful roommates help me relate to the song) Brutal is broader. The song is about the anxieties about growing up going from teenagehood to adulthood. The song details things like parallels parking and not even making to the legal drinking age, things every young person struggles. It’s angst, frustration and angry, at least in tone, but its also genderless. It’s not specifically about female rage, which makes it even more attractive to Gen Z who embraces the non-binary more then any other generation.

While artists like Taylor Swift and Avril Lavigne have expressed anger and revenge from a young girl’s perspective in their music, Rodrigo goes it differently. Rodrigo is unbridled, unhinged and willing to do whatever it takes. She’s just as spiteful as “Picture To Burn,” but she is unhinged in a way that only film characters are, like Promising Young Woman’s Cassandra Thomas, Suicide Squad’s Harley Quinn, Jennifer’s Body’s Jennifer Check, Harry Potter’s Bellatrix Lestrange, Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne and A Simple Favor’s Emily Nelson. Swift is also a bit restrained, only expressing anger or fantasizing about revenge, not actually going through with it.

Things are different now. The response to Rodrigo’s energetic celebration of rage also vastly differs from the response to Jennifer’s Body and Taylor Swift’s, mostly because she isn’t alone. Promising Young Woman, the Oscar-winning film that combats rape culture head on is the 2020, adult contemporary equivalent to Jennifer’s Body and Rodrigo’s ”good 4 u” is the modern equivalent of Swift’s “Picture To Burn,” but unlike Swift, Rodrigo has peers that are just as sad, resentful, spiteful and angry as her like Willow and Billie Eilish. Rodrigo is making a case for feminine rage as a legitimate art worthy of expression, and its undeniably relatable, and that is not just proven by the fact its a #1 hit. While Swift and Jennifer’s Body may have shown girls that feeling anger, an emotion they using hold in, push away and quietly extinguish, is okay, but Rodrigo’s “good 4 u is the first time they have truly heard it and fully expect it, and so has society.

Do Revenge was a recent Netflix film that dealt with teenage female rage in the same vein as Jennifer’s Body and Olivia Rodrigo (the voiceover line “but I’m a teenage girl. We’re psychopaths” reeks of Jennifer’s Body and Rodrigo was even on the film’s soundtrack). The interesting thing about Rodrigo’s music video visuals, Do Revenge, Last Night In Soho and Promising Young Woman is that the female rage in these films is juxtaposed with neon, candy-colored cinematography, which I think is very important to take note of. Color, and specifically pastel shades, are often associated with innocence and femininity, which in the horror and teen genres, and in society itself, are both demonized. This choice to use these candy-colored color palettes could be interpreted as to visually showing these female characters taking the power back from the men and a society that demonizes their femininity.

Rodrigo may have been the trailblazer for female rage being a theme in music, but was certainly not the first or the last to hop on the trend. As aforementioned, Swift is no stranger to talking about anger in her music. Her first showcase of this were in the songs “Should’ve Said No” and mainly “Picture To Burn” on her debut album. Her second album featured the angry song “Forever & Always.” The thing that all of these songs have in common are that they all surround heartbreak about a boy. It’s not vengeful or validating, it’s very matter-of-fact saying “you broke my heart and now I am pissed,” instead of saying the far more fun and fanatical “you broke my heart and you aren’t gonna get away with it.”

Swifties have proclaimed “Swiftie first, feminist second,” in regards to her angry anthem “Better Than Revenge,” the fan-favorite track on her 3rd album. This is song is controversial because it talks about girl-on-girl competition instead of support and the idea of competing for a guy. The imagery in the song also has parallels to the first few episodes to Gossip Girl with the first verse describing Serena from Blair’s perspective and the second verse describing Blair from Serena’s perspective, though this is a theory. It also has been perceived as sex-negative with slut-shaming undertone with lyrics that say “known for the things that she does on the mattress.” However, Swift identifies as a feminist and in defense of the song says that the song is clearly about teenage love, when you re at the age when you think someone can steal someone else form you, instead of people just growing apart. At its core, it’s a song about female rage, although still with Swift’s constant theme of having a boy as the subject of her anger.

Swift has said numerous times that she considered her album Red as her one true break-up album, which means it has a plethora of songs dealing with anger, as it is a valid stage during a break-up. Songs like “I Knew You Were Trouble,” which deal with self-loathing and regret, “We Are Never Getting Back Together,” and even parts of her fan favorite “All Too Well” all deal with anger, however, they still deal with having a man at the center.

1989 was a shift in Swift’s angry lyrics. “Bad Blood,” although perceived as being about her feud with Katy Perry and therefore sparking debate over how feminist the song really is (although, this is absurd because its unrealistic to say that women can’t disagree with each other, however, if you look at the lyrics, they are quite genderless. They aren’t talking about heartbreak, they are talking about betrayal, which can be about anyone. A friend. A relative. A roommate. A coworker. This was the first time she was unapologetic about her anger. She was even assertive and confrontational about it.

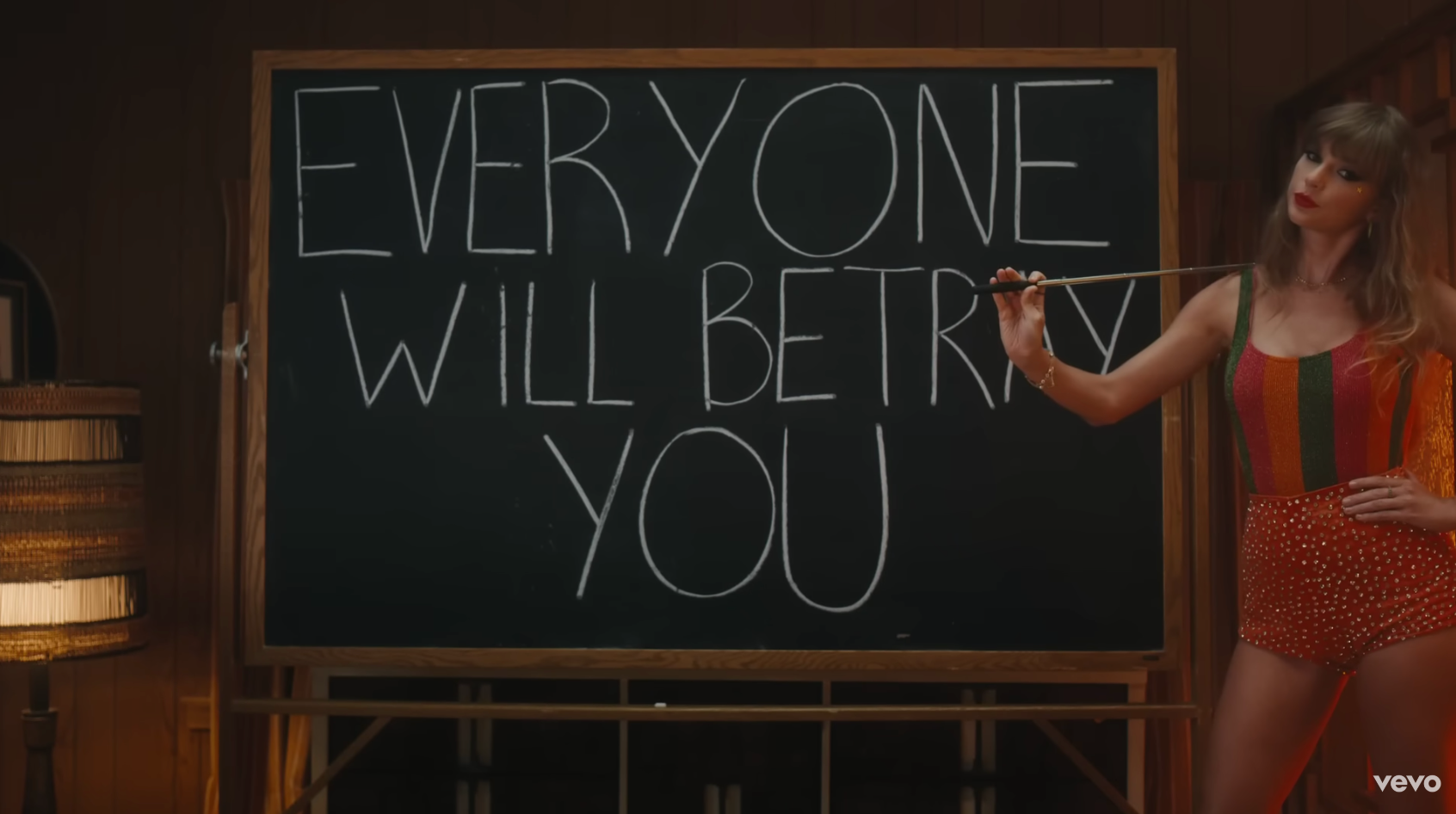

Reputation was just an anger album altogether. Swift called out the media, Kanye West, who she has a notable feud with, sexism, and the haters. “Look What You Made Me Do” was the inaugural single for the era, and it was undeniably a rage-fueled diss track, and an epic comeback. “This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things” uses themes of glitz and glamour and peels back the layers of the manipulative underneath, similar to Hollywood. Both these songs hint at the feud with West.

Her album Lover didn’t deal much with anger, as it was overall a very lighthearted, playful album. It did call out injustices such as inequality in regard to the LGBTQ+ community and mainly the theme of sexism in our society.

Her pandemic album, Folklore had one of Swift’s first blatantly femininely angry songs to date, not caused by heartbreak or betrayal, but simply just female anger, something that is often taboo in society due to sexism. Folklore’s track 12, Mad Woman, is literally about female rage. It’s about a woman getting gaslighted, but also about a woman getting joyous revenge on a town that ostracizes her. Her collaboration partner Aaron Dessner of the band The National, who was featured on Evermore, came up an instrumental that Swift thought sounded like female rage, which inspired her to write a song about that theme. The theme of gaslighting the song was because of Swift’s own past with gaslighting and rage-inducing the experience was for her. She uses the imagery of witch hunts in the song, possibly a reference to the witches in Macbeth or Medea from Medea, which is some of the first and most well-known depictions of female rage from media before the 1800s.

Some of the lyrics that most blatantly discuss female rage are “And there’s nothing like a mad woman / What a shame she went mad / No one likes a mad woman / You made her like that.” and “You poke that bear til the claws come out / And you find something to wrap your noose around.” The former describes the taboo of female rage in society in Swift renowned poetic way. Society tells women not to get angry, but when they do they shame them and treat them as ‘crazy,’ when it’s society’s stigmas and constructs that made her that way, like the insane debates about abortion and women’s rights. While, the latter is similar to the saying “if a boy is mean to you, it means they like you,” but instead it reveals the truth behind this false saying. Society pushes women around and when they speak up about it or confront it, they are punished.

Post-Folklore songs from Swift that deal with female rage are Evermore’s “No Body, No Crime,” a Gone Girl-esque tale about a group of women banning together to get revenge on a friends unfaithful partner, basically the adult version of ‘Better than Revenge,” and Midnights’ “Vigilante Shit,” which has way more nonchalant and confident idea of female rage with lyrics like “lately I’m dressing for revenge,” and detailing a “Karma’s a bitch” mindset when enemies former wife reveals she actually likes her (hinting at Kim Kardashian). In the former song, Swift is clearly still angry, but she is also more at peace, letting karma to its job, as told in the Midnights track ‘Karma,” but that doesn’t mean he does get small moments of satisfying joy when she dresses to kill knowing her enemies will see it. Also, Swift revealed prior to the album’s release that one of the things that keep her up at night is fantasizing about revenge, something angry girls do all the time (so all girls).

Alanis Morisette’s track “You Oughta Know” from her iconic breakup album Jagged Little Pill is one of the most iconic break-ups, female rage songs of all time with frank lyrics like “Is she perverted like me? Would she go down on you in a theater?,” and “It was a slap in the face How quickly I was replaced and are you thinking of me when you fuck her?”. It’s no coincidence with lyrics like this that she and Rodrigo were partnered up for a conversation while participating in Rolling Stone’s Musicians on Musicians, where they even talked about the power of anger. No Doubt, Gwen Stefani’s 90s band, had a song called “Just A Girl,” which went against societal norms and dared to say how cool it is to be a girl, despite what society says. Bikini Kill, Rihanna, Joan Jett, TLC, Hole, Sia, Avril Lavigne, Paramore, Adele, Rei Ami and Lily Allen are all also artists who have explored female rage, but never in the ways, Swift and Rodrigo explored it through “good 4 u” “Brutal” and “Mad Woman.”

This trend has also found its way into our TV. Madison Montgomery from American Horror Story: Coven was so angry after her assault that he flipped a bus of jocks with her mind. Kevin Can Fuck Himself, starring Schitt’s Creek’s Annie Murphy, is a genre-blending show about a woman getting revenge on her misogynistic husband and finding power in her anger. Ryan Murphy has depicted feminine rage in his popular projects like Glee, through many unapologetically girly power ballads, especially from Naya Rivera, Jenna Ushkowitz and Dianna Argon’s characters, Scream Queens, mainly through Emma Robert’s iconic character Chanel Oberlin, The Politician, Feud: Bette and Joan, American Horror Story and American Crime Story, main the Impeachment season. Maid, which was produced by female rage queen Margot Robbie through her wild roles in I, Tonya, her recent film Babylon and ravishingly unhinged portrayal of Harley Quinn, also dealt with female rage. In the last season of Succession, Sarah Snook’s Siobhan Roy was seen spitting in Kendall’s notebook after he humiliated her to the tune of Nirvana’s “Rape Me.” Sharp Objects utilizes female rage through Eliza Scanlen’s character. Euphoria, Yellowjackets and Killing Eve are three prestige shows that have female rage at their story’s core. All have been nominated and won Emmys, among other prestigious awards. Zendaya’s Rue, Hunter Schafer’s Jules, Alexa Demie’s Maddy and Sydney Sweeney’s Cassie are the most rage-fueled female characters on the show. The dream sequence of Rue and Jules burning Nate alive and shooting at him is proof. Fleabag’s Phoebe Waller-Bridge, creator of Killing Eve told Vogue that female rage is a theme that interests her, just like Rodrigo said. And based on massively popular these projects are, its seems audiences are also endlessly fascinated by it.

Yellowjackets isn’t the only teen drama to use the theme of feminine rage. In Riverdale’s beloved first season featured a smash-the-patriarchy episode that was fueled by feminine rage. It’s angriest character, Cheryl Blossom is also a female rage figure, often pulling a Rodrigo and committing arson or declaring “she’s in the mood for chaos.” Katherine Pierce may be the quintessential villain of The Vampire Diaries, buts he’s also a fan-favorite due to her confidence, and anger-fueled revenge schemes that are combined with a girly, seductive flare. Recent hit Cruel Summer depicted female rage from two rival girls’ perspectives, one who was accused of something criminal they didn’t do and one who was traumatized after being groomed, coerced and kidnapped by an older man. Euphoria’s Maddy is often seen throwing girls’ heads against the wall in fits of anger, usually because of betrayal or racism, and often as a form of lashing out due to her toxic relationship with Nate. Euphoria’s Cassie was fuming at her sister’s play that she creepily fogged up a window in one of the scariest ghosts in the show’s history. Blair Waldorf’s schemes on Gossip Girl were often fueled by feminine rage, however the lack of conversation surrounding it may cause those to be perceived as otherwise. Her scheming could also be perceived as her lashing out because of this internal resentment of anger due to the pressure she puts on herself to be the perfect high-society woman. Pretty Little Liars also used female rage at some moment, and its reboot Pretty Littel Liars: Original Sin. The reboot used it more since rape-revenge was the theme throughout the first season. However, I think Sex Education is the teen drama to showcase female rage best.

In the second season of the Netflix hit, fan-favorite Aimee Gibbs gets sexual assaulted on the bus. During a Breakfast Club-like attempted bonding session between her classmates, she makes a confession about what happened, her with best friend Maeve, the school badass, being the only one to know prior. She is showed to find out that her classmates have similar experiences. After detention, they decided that they need to let out all of their anger, so they go to a junkyard and beat up an old car. At the beginning of the scene, Aimee is apprehensive about hitting the car, but as the scene progresses and her classmates’ cheer her one, she grows more empowered. The rest of her classmates eventually join in. The next day, her classmates gather at Aimee’s local bus stop in an effort to use female camaraderie to help her feel safe enough to take the bus again. The episode was widely regarded as one of the best episodes of 2020.

Unlike Sex Education, Succession’s Shiv Roy, Killing Eve’s Villanelle and Euphoria’s Rue Bennett are all considered antiheroines. However, their rage isn’t what makes them antiheroic. It’s Shiv’s privilege, Villanelle, morality and Rue’s addiction that makes them hateable, showing how valid female rage really is, even if it’s not viewed that way by society.

Only recently have been able to see gritty female fight scenes and in-depth character studies on flawed women, without the goal to make them perfect. The goal is simply to learn, relate and empathize. After all, antiheroes like Don Draper and Tony Sopranos have garnered that reaction out of viewers for decades now. Why can’t antiheroines? After all, our flaws are what makes us human, right?

This influx in antiheroines is due to how identifiable these characters are to the viewer, whether we want to admit it or not. That’s what being human means. Viewers are curious about antiheroic characters. Those who do bad things for good reasons and those who do good things for bad reasons. We enjoy seeing what people are capable of, and since women are often pushed towards a palace of submission, that makes antiheroic women immensely more fascinating because they are pushing back against the patriarchy, and while that’s a good thing, for these characters its for morally gray reasons. That’s also this antiheroine trend should be here to stay, because its about time multi-faceted, complex and flawed beings shown in media are the norm, not a rarity.

This immoral behavior these characters employ may be brutal (Rodrigo’s pun unintended), but you can’t deny ist relatable. It allows the female viewer to live vicariously, imagining the characters are doing what they are doing to our real life enemies. Its almost therapeutic to watch this kind of content because society dismisses our rage so much.

This trend can also be linked to the “feminine urge” meme that took over 2021, the tear when female rage content really took off. Women often have the internal urge to slap their ex who betrays them or scream when life gets rough, but society conditions us not to. The feminine urge allows us to feel those feelings. It utilized the rare positive element of social media, camaraderie. We felt less alone knowing other women feel the same urges as we do, no matter how honest and funny they are. These female rage characters personality this feminine urge; this feminine urge to be angry

These personifications broaden the meaning of femininity, showing unprecedented aspects of what its like to be a woman. Its helps use finds solidarity. Frankly, this female rage trend throughout media is long overdue. Its made up for it’s lack thereof throughout pop culture history. And its definitely not a coincidence that the influx of female directors from Greta Gerwig to Olivia Wilde has coincided with the trend (also Greta Gerwig has hinted at the female rage in her films, especially in Lady Bird).

It’s also worth noting that the female rage genre has almost exclusively featured white women, with only Hidden Figures and Euphoria being the most notable examples of showing feminine rage in women of color. This often due to the “angry black girl” stereotype and many trying to veer away from it. However, when done well, like in Hidden Figures and Euphoria, if brings some of the most iconic and powerful performances from actresses of color, with Taraji P. Henson and Zendaya giving award-worthy performances. However, again, these are both Black women. There are almost no mainstream examples of other WOC showcased in female rage, unless you count Olivia Rodrigo being of Filipino descent her music, as aforementioned, being providing the feminine rage soundtrack for Gen Z.

The question is; why has this just recently become the trend? Well, as women know, we have so much to be angry about, but especially now. This summer, the Supreme Court reversed Roe V. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court that legalized abortion, a basic human right, in the 1970s. Birth control is a hot-button topic among conservative politicians, who are mostly vagina-less. We also had to endure 4 years of having our president be a sexist, racist, misogynistic predator with a history of infidelity and rape. Is it any wonder that we are PISSED?!

And this is after the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements, which finally normalized outing men for their predatory and inappropriate behavior including, but not limited to, pedophilia, rape, sexual violence, domestic violence, workplace harassment and child pornography. This was supposed to be silence-breaking and revolutionary, and in some aspects it was. It got predators like Jeffery Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, Kevin Spacey and R, Kelley off the streets. However, the reversal of Roe V. Wade shouldn’t have been possible post-#MeToo.

The thing with rage, of any kind, is that true expression of it only lasts a short time, although the feeling can manifest in resentment and grudges for decades to come. However, feminine rage is more unique in the long-term because feminine rage is actually an example of feminine resilience. We get pushed down by society over and over again, and yet we always get back up. We speak up against this society. We encourage other women and create camaraderie and support. This cycle further shows that while women may look like pretty princesses, in reality, we are warriors. We are more resilient creatures on Earth then any prey in the wild.

Due to these scary times, female rage stories provide a form of catharsis. This validates our feelings and makes them socially acceptable. Of course, this shouldn’t be the case at all. This isn’t the 1950s. Abortion and birth control are basic human rights. We don’t deserve to walk throughout the world worried that a man will attack us and traumatize us, a man fully capable of keeping his dick in his pants. But, since that’s the world we live in, at least we get to live vicariously through Villanelle’s antics and Jennifer Check’s revenge.