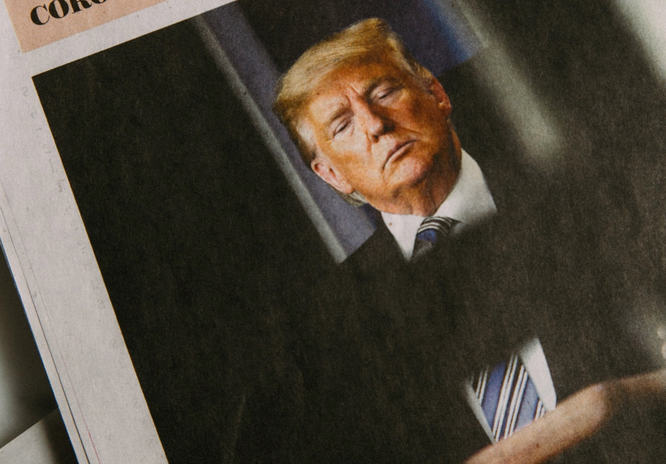

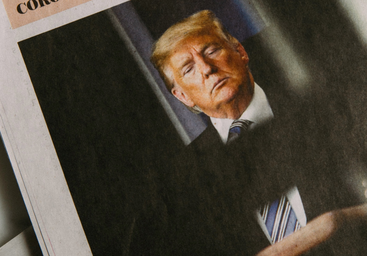

In late December 2023, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled former President Donald Trump’s candidacy to get back into the White House ineligible, and removed him from Colorado’s presidential primary ballot.

Expectedly, Trump did not take this ruling without a fight–and the case will be reviewed for legitimacy by the Supreme Court of the United States on February 8, 2024. The ruling was fast-tracked to be decided before Colorado’s primary election in March, and the results of the Supreme Court’s decision will, undoubtedly, help decide who walks into the White House as Commander in Chief come January of next year.

If your response to this suit against Trump is something along the lines of, “I didn’t know they could do that”, you are not alone.

The amendment in question is the 14th, ratified in 1868 after the American Civil War. Of the three amendments passed, now known as the Reconstruction Amendment, the Fourteenth’s purpose is the most ambiguous. The Thirteenth Amendment prohibits slavery, albeit not entirely. The Fifteenth Amendment extended suffrage to Black American men…albeit, not entirely.

The Fourteenth Amendment, however, has multiple policies. It holds that all persons born on United States soil are United States citizens. It holds that every citizen is entitled to equal protection under the law. It is a loaded document, to say the very least. It has been used to protect people of color’s rights, abortion rights, worker’s rights, immigrant rights, and many, many more.

Now, it is being attempted to use it to remove Donald Trump from our ballots, because of a seldom discussed Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which reads as follows:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

This section was written immediately after the American Civil War, with the goal of keeping Confederate figures out of office. It says any citizen holding civil or military office (although it doesn’t directly mention the presidency) in the United States shall not have been involved or any insurrection or rebellion against the United States, in any form. The amendment was written in response to Confederate succession, which is the most infamous example of insurrection, defined as a violent uprising against the government, in the United States to this day.

To draw a clear and simple line from Civil War politics to now–Former President Trump engaged in (according to some courts) the infamous insurrection on the Capitol on January 6, 2021, so the 14th Amendment could be used to stop Donald Trump’s 2024 Presidential run.

Will it? It’s still unclear.

Some legal scholars have doubts about applying Section 3 to Trump’s case. Samuel Moyn, a professor of law at Yale, says that “The Supreme Court cannot bring the fantasy [that Donald Trump was not a top candidate for the presidency] into being”. Per Moyn, there are too many factors contested in Trump’s case–his involvement in January 6th, especially.

Moyn also warns that a case that bars someone from running for office may set a dangerous precedent of power from the Supreme Court. Not to mention, Trump’s following didn’t accept Biden’s win in 2020, and the results were violent–so what could happen if the government bars him from running at all? Moyn argues that “The purpose of Section 3 was to stabilize the country after a civil war”, and this Supreme Court case could cause another one.

There’s also confusion about if Section 3 even applies to the presidential seat. Expert on the 14th amendment Kurt Lash says it doesn’t–and that the section was written for more local offices, where Confederates might be able to get popular among residents. On the other hand, the Colorado Supreme Court says that Section 3 absolutely includes the presidency:

“[It would not make sense that] Section 3 disqualifies every oath-breaking insurrectionist except the most powerful one and that it bars oath breakers from virtually every office, both state and federal, except the highest one in the land. Both results are inconsistent with the plain language and history of Section 3.”

There are many articles by accomplished scholars out there who agree with the ruling of the Colorado case, and think the current political circus that is the 2024 election is exactly what Section 3 was made for. However, there seems to be no consensus out there, even for the most liberal legal scholars.

So, what’s the takeaway? It’s not my call–it’s the Supreme Courts’.

But this case is a historic one, and it’s bringing a lot of ideas, questions, and theories out of the woodwork that have been dormant for hundreds of years.

Does the government have no power to stop a man with 91 felonies from becoming our Commander in Chief? If they do, could they use that power to stop others in the future, who may not deserve the ugly label of “insurrectionist” that has been stamped across so many of our leader’s foreheads?

I fear the sheer exhaustion of the Trump news cycle, that has been ringing in ears since 2016, has numbed our nation into not fully understanding, or trying to understand, the most recent legal actions taken against former President Donald Trump.

Even as a political science student, I had to groggily rub my eyes and rise from my metaphorical bed of burnout from political fights, scandals, and yes, insurrections, to even register the implications of this case.

But, this case is worth getting out of bed for. Even if the Supreme Court decides to allow President Trump on the ballot–which may very well happen–it leaves the most foreboding barrier to another Trump presidency out there: the electorate.

Where our government may not have the capacity to condemn Donald Trump’s actions, the people do. They did in 2020.

I am not saying our electoral system is perfect, or that I don’t fear another heartbreaking, terrifying display of how a democratic system shouldn’t work come November. I absolutely do, and voting isn’t the end-all, be-all solution.

What I am saying is that while the case decision might seem disappointing for some (myself included) if it is decided Trump can be on the ballot, a pro-Trump decision would imply power of the electorate over the government still. There’s hope to be found still.

If this case ends with Trump’s name on our ballot, it might just need to serve a reminder of the faith former leaders had in our votes, our judgement, when they wrote our laws.

But, of course, that faith only works if you do what you know you need to do on November 5, 2024.