If your friends all jumped off a cliff, would you jump too?

Sixty years ago, German-American historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt was sent to Jerusalem to get the scoop on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi party leader during WWII who was in part responsible for the death of over 6 million people. Arendt, a Jewish, German immigrant displaced to America as a result of the war, nervously yet eagerly awaited when she would first get to observe Eichmann. Would he look like a monster? Would he act violently and be filled with anger? Most of all, would he show any remorse for his actions during the war that contributed to the mass genocide of her people?

What she discovered was indeed a shock, but not in the way anyone would have expected: Eichmann was just a regular guy. He wasn’t particularly good looking (or ugly), definitely wasn’t some kind of genius or mastermind, and seemed pretty much indifferent when faced with his past atrocities. She observed that he saw his actions as unexceptional, and just what had happened when he had “gone with the flow”, so to speak. He wasn’t really deeply thinking about the crimes against humanity which were being committed through his actions: Eichmann was just continuing on as he perceived society implored him to.

This shocking revelation about Eichmann’s court case led Arendt to coin a new term for the social condition she believed was responsible for creating circumstances such as this. She called it “the banality of evil”. Banality, or the condition of being boring, ordinary, and unoriginal, is not a word most people would use to describe evil. However, according to Judith Butler with The Guardian, “she feared that what had become ‘banal’ was non-thinking itself,” (Butler 2011). By describing the actions of Eichmann and others involved in the genocide as banal, Arendt illustrated the mob mentality which had led to the complete absence of morals and a sort of “well, they’re doing it, so it must be okay!” mindset which drove many of the atrocities committed during the 1930’s and 1940’s. Arendt saw a pattern of banality, present throughout human history, and theorized acts of evil can indeed become banal, namely when they are conducted by a group that is susceptible to strong feelings of protectiveness and self preservation.

While the Holocaust was nearly 100 years ago, and Arendt’s observations about the trial took place not long afterwards, the “banality of evil” has remained prominent in today’s political sphere. The presence of social media and keyboard warriors has made it seem okay for people to post their wild, completely out of pocket opinions online, and the anonymity that comes with hiding behind a screen has made it easy for others to simply agree. Think about it this way– liking a political post on Instagram, or reposting an infographic to your story seems pretty routine for most of us at this point. But what about the posts that are promoting hate speech, or inciting violent and explosive reactions from those who may be exposed to them? Someone could be thinking, “well, since some people are posting political opinions, that means I should be able to too!” and then come through with a tweet invalidating an entire population of people (cough JK Rowling cough cough), and it just becomes, well, banal. Because it’s what is expected, what everyone is doing. But that shouldn’t make it okay.

https://x.com/jk_rowling/status/1775187763995824350?s=20

According to recent research by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, roughly one-third of all internet users have experienced hate speech. You might be thinking– this is just on the internet, not a real life issue that I should be worrying about every day. However, while the internet has certainly made it easier to be a bystander to extremes such as hate speech and cyber-bullying, that by no means limits it to only being online.

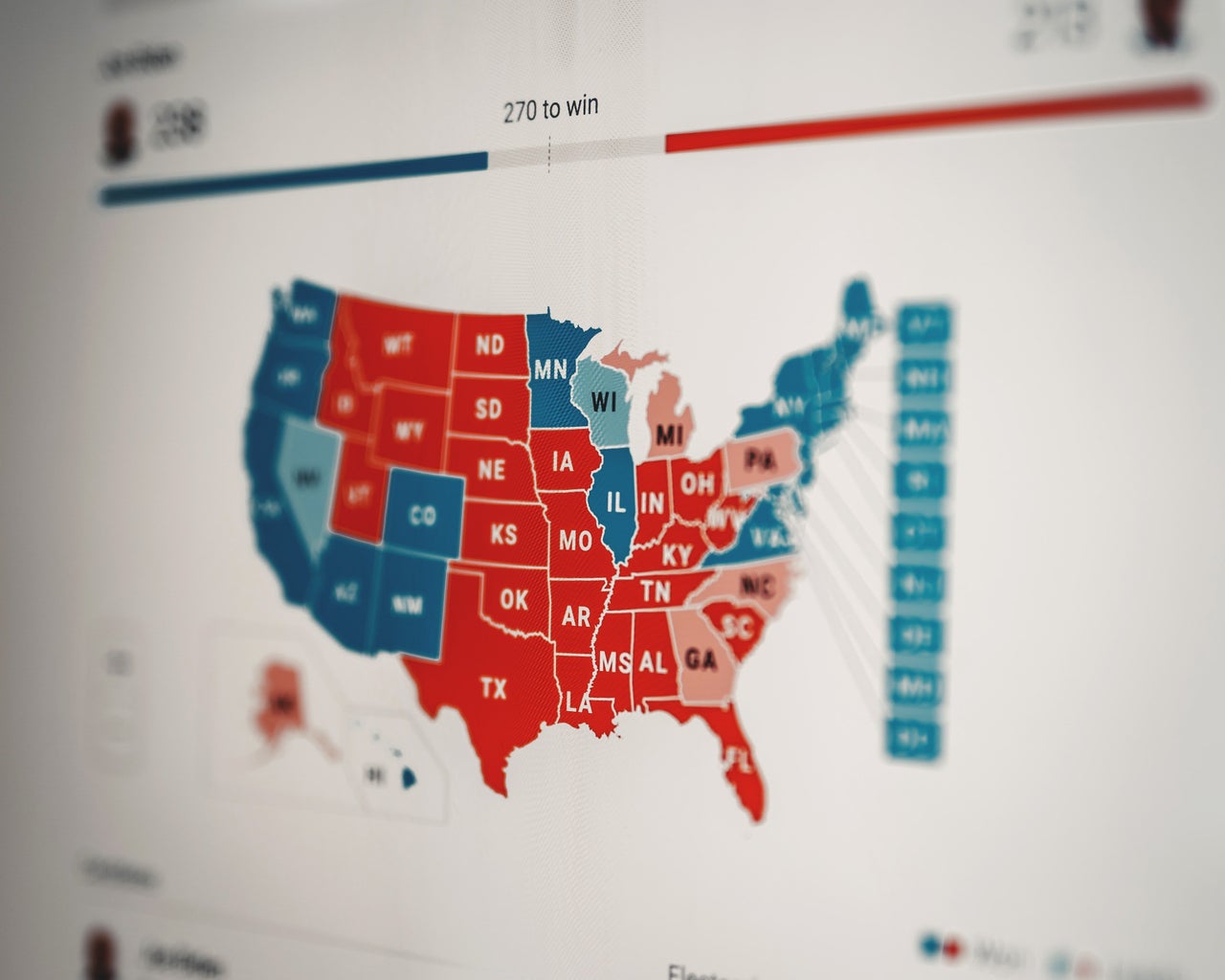

One of President George Washington’s biggest hopes for a successful democracy in our country was to avoid the two-party system. He wanted to avoid the possibility of “loyalty voting,” or voting for a candidate simply because they’re part of the political party that a person has always identified with, rather than the candidate’s actual beliefs and policies. Washington’s fears were that America would fall into a generations-long cycle of banality; a process of nonthinking that could result in unfit figures of authority in our government. Clearly, we failed to heed his advice, and now we have that very problem. Recently, the US has seen an increase in radical ideologies from both sides of the political scale. In reality, most people in the US are not as extreme as our politicians may make us seem; in fact, most Americans would describe themselves as moderate, as opposed to extremely liberal or conservative. So, why don’t our figures of authority match this number? Because, rather than doing the research and actually learning about candidates’ core beliefs, most Americans either check the box for “Democrat” or “Republican” candidates. Because of this, we end up with radical politicians that get away with doing and saying insane things. In recent years, we’ve seen a huge increase in political hate speech directed towards vulnerable groups such as immigrants, the LGBTQIA+ community, and people of color, all because voters aren’t taking the time to actually think about the people they’re voting for, just going along with whatever their assigned political party is telling them is best.By viewing voting as a banal, activity that can be done on auto-pilot, we have created an environment that lets aggressive and hateful rhetorics thrive.

When we think of banality, we think of going to school, making a sandwich, brushing our teeth. We don’t think about promoting hate speech or participating in a national uprising as routine, boring, or unoriginal. However, when we take a closer look, it becomes obvious how quickly “non thinking” and failure to consider consequences can escalate into bigger problems. This is why it’s important to keep in mind the implications of what you are putting out into the world. By remaining mindful of this, we can protect ourselves against the banality of evil, and stop so many crises before they start.