Ross Douthat of The Atlantic once described Lakewood Church preacher, Joel Osteen, as a “self-help [author] on the one hand and [an apostle] of moralistic therapeutic deism on the other, slapping Christian window dressing on how-to guides for upward mobility and psychological satisfaction.” Despite this slightly accusatory character assessment, the megachurch boasts over 50,000 in-person parishioners each week and commands a television audience of over 10 million worldwide. Within the 16,000 square foot amphitheater in Houston, Texas, Osteen proselytizes on an immaculately lit stage to a sea of Lakewood’s disciples, all while sporting a perfectly tailored suit and idyllic white smile. Between musical interludes that mimic a rock concert, his smooth Southern accent professes the truths of the Bible – what “the Lord” really wants us to know – and how we can use the word to reach new heights in our own lives. Interwoven throughout Osteen’s sermons are elements of historical faith practices like the Prosperity Gospel and Christian Science, but all delivered in Middle-America-friendly phraseology. Due to the unanimity of his star power, he guides an army of worshippers toward a closer relationship with God, belief in self-betterment, and, above all, financial allegiance to Joel Osteen, the brand.

Lakewood Church was founded in 1959 by John Osteen and his wife, Dodie, Joel’s parents. They converted an abandoned feed store into a makeshift ministry, attracting locals and tourists alike over the next forty years. When John Osteen died in 1999, Joel and his wife, Victoria, took responsibility as the new face of Lakewood Church. With a formal education in television broadcasting, Osteen’s lack of divinity training was seemingly eclipsed by his keen ability to attract an audience. By 2003, the church had flourished, and soon acquired its current location, the Compaq Center, prior home of the Houston Rockets. Under his leadership, Osteen has managed to grow the church in both size and scope, becoming the largest megachurch in the United States by 2016. Together with the reach of various broadcasting arms including television and satellite radio stations, this measure grows exponentially. Additionally, as Lakewood Church expanded, so did the Joel Osteen persona. As of 2020, the pastor has authored fourteen books and garnered the title of New York Times bestselling author. Through it all, Osteen, and his supporting cast, remain true to a “core message”: “Our God is a good God who has good plans for those who choose to follow Jesus and are faithful and obedient to God’s Word.”

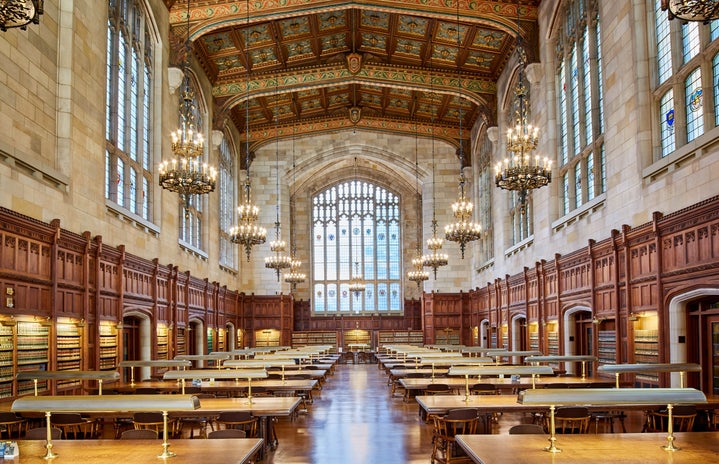

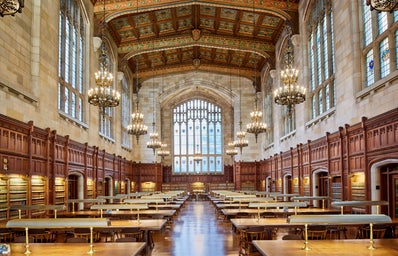

On November 15th, I attended the “Sunday Service” at Lakewood Church, virtually via the livestream, due to COVID-19. Raised in a Catholic home, I was unsure of what to expect from a “non-denominational, evangelical Christian church.” While my faith is similar in terms of creed, the preaching and practice of worship at Lakewood radically diverged from mine. I was immediately astonished by the glamour of the situation. Compared to the small, local church in which I was confirmed, complete with stained-glass windows and kneelers in each pew, the size and ambiance of the Compaq Center stood in stark contrast. From this perspective, the service felt much more like a Ted Talk, or even a concert, than a weekly religious gathering. Prior to mass, jumbotrons displayed promotional ads targeting incoming parishioners. Whether promoting the sale of Osteen’s latest book or providing detailed instructions and QR codes for fielding donations, the monetized aspect of the place was palpable, even through a screen. As the lights began to dim, a full band emerged on stage. Spotlights circled, and the band began to play what initially sounded like a Billboard Hot 100 song but culminated in a chorus about an overwhelming love for Jesus. After a flurry of applause and an anticipatory drumroll, Joel and Victoria emerged to deliver brief opening remarks. Righteously waving a fist in the air, Osteen professed that “Not one of us is going to leave the same way we came in. You’re gonna go out of here with more joy, more faith, more victory!” Immediately, the overt enthusiasm piqued my interest. At the Catholic services I have attended in the past, the mood is quiet, reflective, and almost somber. While there is certainly no five-piece band, there is definitely no fist-shaking, applauding, or cheering, either. Lakewood’s response to Osteen’s stage presence was odd to me but highlighted his star power, nonetheless.

While the service, as a whole, ran nearly a full two hours, sermons and speeches filled only half of that time. The rest was dedicated to bombastic musical interludes or calls for donations. These breaks seemed to serve as “intermissions” for the preachers. Around the one hour mark, the lights dimmed as a segment featuring Lakewood Church member, Anita Daniels, played on screens. A Christ-denier turned zealot, she shared her story of “redemption” and how she found “salvation” within the church. Now, she explained, she uses her good faith to run an affordable housing and disaster relief non-profit, all in the name of God. As the interview concluded, a check (of an undisclosed amount) was bestowed upon Daniels “on behalf of Pastor Joel, Victoria, and the entire Lakewood community.” This story echoed the common themes of empathy, goodwill, and generosity expressed within the service’s speeches. Again though, these sentiments hinged more on self-help and commercialism than true religious work. When Anita’s piece came to an end, a booming voice came over the speakers, suggesting that in order for Lakewood to support folks like her, more parishioners needed to “lend to the lord,” and, eventually, “he will repay you.” Never before had I experienced a worship service that so overtly emphasized financial gain, in all aspects. Juxtaposed with this custom, a traditional Catholic mass entailed a single “collection” in which small wicker baskets would be passed down pews. Usually, people would offer loose change and, occasionally, my mother would hand me a five dollar bill to drop in the basket.

Aside from the window dressing that included songs, stories, and advertisements, the sermons struck me as the most divergent aspect of the experience. When Osteen emerges for a near forty-minute sermon, he does so with a megawatt smile and a stage presence that renders the audience starstruck, standing and cheering and hanging on his every syllable. When he gets to talking, in a charming, slightly-Southern twang, he focuses not so much on what the Bible really says but rather what it means to all of us. One segment of the sermon references “Luke, Chapter 19,” without any actual reference to “Luke, Chapter 19.” Instead, the highlights are paraphrased, and an entirely unique, non-Biblical conclusion is drawn: “Maybe you’re coming up short as a husband. Maybe you’re coming up short as a wife. Maybe you’re coming up short at work. Maybe you’re coming up short in your finances. Let me remind you that God has placed divinely planted trees in your life right now.” The moral of this story was that blessings are ahead, and God wants each of us to prosper. The curious discussion of finances, one that finds footing time and time again during the mass, differs significantly from other Christian services. Never once has the priest at my church mentioned “work” or “finances” during his homily. Lakewood’s weekly teachings follow the common logic of the Prosperity Gospel, defined as “An aberrant theology that teaches God rewards faith—and hefty tithing—with financial blessings, the prosperity gospel was closely associated with prominent 1980s televangelists […] and is part and parcel of many of today’s charismatic movements in the Global South.” It’s no secret that every facet of Lakewood’s premise is monetized. For this reason, when Osteen takes a minute mid-mass to endorse his latest bestseller, audiences listen as if it is the word of the Lord: “Don’t forget I’ve got a new book out, called Empty Out the Negative. […] I think it will help you.” With a shameless plug for his own self-help book, Osteen manipulates a devout religious audience into his customer base, hawking a product for his financial benefit under the guise that if they follow God, they too can enjoy the splendor of the bounty. It’s no surprise that his millions of viewers – many discouraged, blue-collar Americans – cling to this idea of upward mobility through demonstration of faith. From the outset, the highly-glamorized component of Sunday Service is readily apparent. However, as the sermons begin, there is an undeniable emphasis on wealth – having it, losing it, praying for it – and the ways in which God, and worshipping at Lakewood, can bring it to you.

A thematic undercurrent, prevalent in these times, was the reality of the pandemic. Services at Lakewood’s Houston facility are at very limited capacity, and most parishioners seemed to adhere to the mask guidelines. Despite precautions taken by the organization, Osteen’s messaging seemed to contradict the human role in fighting the virus. He begins his preaching with a note of gratitude: “[We appreciate] you all coming out during a pandemic. We’re taking good care of you, but, mainly, we know God’s watching after you.” As the toll of this deadly disease rises each day in the United States, Osteen’s messaging seems to deny that this is all a work of the divine. He claims that Lakewood’s safety efforts are secondary, given the overarching protection of our health by the Lord. He goes on to discuss David’s words in Psalm 27 and the concept of invisibility. Simplifying the concepts for day-to-day life, Osteen professes that “[God] didn’t say we would never have problems, but he did promise when trouble comes, he will hide you.” While this sweeping statement, again, draws and professes a certain conclusion from the actual scripture, it is filled with the trademark Lakewood spirit of unflinching optimism. However, Osteen goes on to say that “when that cancer looks like it’s going to leave you defeated, God can make you invisible to the cancer.” I was floored by these remarks. In a time of national mourning for the more than 250,000 lives lost from COVID-19, this claim is as dangerous as it is insensitive. This school of thought seems to harken back to Mary Baker Eddy’s dissertation on Christian Science, “Science, Theology, Medicine,” in which she asserts the “Truth” that all healing can be achieved through belief in the divine: “After careful examination of my discovery [of Christian Science], and its demonstration in healing the sick, this fact became evident to me, – that Mind governs the body, not partially, but wholly.” The profession of this thinking – praying away medical issues – left me unnerved, especially in light of the current pandemic. The other worshippers, though, seemed almost revitalized by this assertion, nodding and cheering along in agreement. Perhaps this attitude contributes to the rising infection rates across the nation.

When the Sunday Service concluded, with a standing ovation for Pastor Joel no less, I was left not only historicizing elements of the sermon but also attempting to understand how a man like Osteen had so firmly implanted himself in American consciousness. I began to see a connection between three distinctly American forces… Joel Osteen, President Trump, and the American middle class. The central collision lies in distorted versions of truth, wealth, and discouragement. The struggling middle class are seemingly drawn to Trump for the same reasons they are drawn to Joel Osteen. With the power of celebrity at work, Edward Luce explains that “The more one listens to Osteen, the harder it is to shut out Trump. […] People often ask why so many blue-collar Americans still support Trump in spite of his failure to transform their economic prospects. […] To many Americans, Trump’s wealth and power are proof of God’s favour. That alone is a reason to support him.” Ironically, no matter the present or future reality of these people, the blind promise of optimism from both Trump and Osteen is enough to garner a cult-like following. Their simplistic rhetoric (Osteen’s sans racism, sexism, and xenophobia) gives many Americans a newfound understanding and a belief to cling to when life gets much too difficult. Luce contends that Osteen, like Trump, is astutely aware of his audience: “[Sunday Service] is more like therapy for a broken middle class.” Both figures have won the hearts, the minds, and the wallets of middle-America through unfounded promises, faulty logic, and the overwhelming power of money and fame.

Attending a Lakewood Church Sunday Service was an eye-opening experience, demonstrating to me, a Catholic, how significantly Christian practices can differ. Recognizing the ideals represented by the Lakewood community is essential to understanding the gospel to which millions of Americans subscribe. Historically speaking, Joel Osteen’s modernization of televangelism, through grandiose live music, multi-million dollar book deals, and a personal SiriusXM radio station, brings concepts like the Prosperity Gospel and Christian Science into the 21st century. While I found it virtually impossible to “buy in” to much of what Osteen promoted, I do believe careful observation of his preaching can serve as a way to better understand how others, both across the nation and abroad, consume and utilize religion on a daily basis.