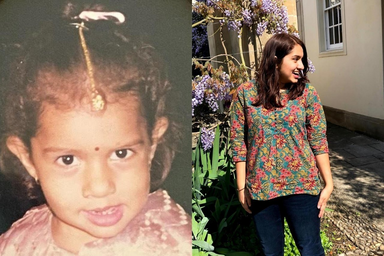

For most of my childhood, all our summer holidays were trips back to India. For two months, my parents, my sister and I would fly out of Dallas or London (wherever we lived at the time) and into New Delhi, to visit the grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins we had there. It was always the highlight of my year. With relatives eager to feed us, give us presents, take us on day trips, and generally shower us with the attention that we preened under, we were spoiled rotten.

And then, each year, we’d fly back, dragging our feet at the thought of going back to school. We’d unpack our new treasures. A fresh set of Indian outfits — lehengas and kurtas, suits and dupattas — would be folded into precariously balanced piles and shoved into the highest shelf of our wardrobe, the excitement of that year’s India trip put away along with them.

If you’ve never shopped for formal clothes in India, I should explain — it’s a bit of an event. You’ll go to a cloth shop, pick the right fabric for your outfits. You’ll have to see a tailor who takes all of your measurements, then wait for weeks while the clothes are handmade. Then you try them on and get adjustments done.

I could spend hours of my time in India waiting for outfits to be made, but as soon as I came back home, I was determined that no one would see me in them.

India is a country of one billion people, but to me, it always felt like a secret I had to keep private. Weekends and nights at home were fair game — family Bollywood film nights, dal and roti for dinner. But back at school and with my friends, it was something I carefully talked around. Even at eight or nine years old, I would preemptively cringe at the thought of discussing my trips to India, or the fact that I’d been born there. I would play the whole conversation in my head beforehand:

“No, we don’t ride to school on elephants.”

“I’m not going to be sold into marriage as a child bride.”

“My parents aren’t forcing me to be a doctor.”

All the possibilities exhausted and embarrassed me, and I didn’t want to deal with it. I had my moments, sure — if people came over to my house, my mother would sometimes let us each wear a bindi or offer to do henna on our hands, and I thrived knowing how exciting my friends found it. But it was one thing showing off the aspects of Indian culture I knew my white friends would find exotic and exciting, like a cool accessory, and another entirely to try to navigate explaining it to people as my “normal.”

It was a constant balancing act, keeping “Indian me” and “normal me” as two separate entities, one which I spent years practicing and perfecting.

As you can imagine, I was pretty frustrated when we ended up moving back to India when I was 14. The boundaries I’d spent my whole life curating, subconsciously or otherwise, became completely irrelevant and my whole sense of self turned inside out. I went from being “the Indian one” in a Western setting to being “the Westernized one” in India. I went to an international school. I made friends with expats. I became, for all intents and purposes, a foreigner in the same country I’d treated as my own hidden origin story.

All the time I’d spent being precious about how I looked to my friends were suddenly irrelevant — the friends I’d made were continents away and whatever constituted “normal” fashion was suddenly completely different. Women on the street wore saris or salwar kameez as often as they did jeans. Even in school, it wasn’t uncommon for my American or English or European friends to turn up in local printed or dyed fabrics, eager to connect with their host country’s culture. Everything about India that I’d treated as a secret too complicated to explain to those around me was suddenly commonplace, making me the outsider. I raided the shelf of “special occasion” clothes every week and I was trussed into anarkalis and churidars and other outfits I had no idea how to wear by myself because suddenly every event demanded it. This only made me more uncomfortable trying to dress for school; without the safety of a school uniform and a long-rehearsed set of outfits to rely on, my early sense of style was best forgotten (let’s just say it involved the words “jorts”, “elasticated” and “Birkenstocks” in the same sentence). Whatever metric I’d used to present myself to the world had quickly fallen apart. I had to wonder if by trying to keep the Indian part of myself hidden away from all my friends, I’d lost my own way to it as well.

Moving to India was my third international move, and three years later when we packed up to go from India to the states, these transitory periods had started to feel like the only constant in my life.

I’d expended so much energy attempting to curate neat little boxes to piece myself into, hoping that everyone would find me cooler, more relatable, and easier to consume that way.

The advantage of so many dramatic and tumultuous relocations was that it forced me to accept that I couldn’t control how other people perceived me, mainly because I had no say in who those other people were. Chasing “normal” became pointless when “normal” was so different for all different groups of people. While my school friends in London wouldn’t go anywhere without several coats of mascara, women in New Delhi were all about kajal and red lipstick; moving to Los Angeles, I quickly discovered contour and highlight were essentials for most people.

I’d like to say it was profound personal self-reflection that made me give up on trying to stick to how other people thought I should dress and act and carry myself but really, it was more that the number of cultural changes wore me out after a while.

I was 17 the first time I wore a kurta to school because L.A. was hot, I missed my friends in India and I was behind on laundry. I was running late getting dressed as usual, so I didn’t really have time to give my wardrobe much thought until I was already in school. When I did realize what I’d done, I panicked. I was already the new kid, and the idea of making myself stick out was deeply uncomfortable. No one said anything, though, and I had to admit it was nice. No one whispered or pointed or laughed — and why would they? There was a girl in my grade who would rock a leather corset each week, another one who would sew her own clothes.

I’d joined my new high school several months into junior year; nobody knew me, and it was too late to hope my “new kid” status would go unnoticed. This was terrifying and lonely, but it meant I was forced to go without other people’s expectations as a crutch. I was forced, for the first time, to think about what normal meant to me. I had no existing guidelines to go by when thinking about how to dress. Three years living in India had reminded me of my connection to my heritage in a way I couldn’t easily shake, and I missed it now that I was gone, once more a stranger in a strange land. At first, the dressing choices I made were like baby blankets or good luck charms, a way to ground me and remind me of the familiar home and environment I’d left behind — a traditional beaded necklace my grandmother had given me thrown over a band t-shirt, a pair of hand-dyed harem pants I’d bought from a market in my grandparent’s town paired with a plain blouse. I came to the gradual realization that these simple choices felt more me than anything I was used to. And no one was pointing or laughing. When people said, “I love your shirt, where did you get it?” I’d say “from India” and feel like it meant something more, something I was proud of.

I ended up back in the U.K. for college, while my family stayed in L.A., and by this point, I leaned into the freedom that came with defining my identity on my own terms, just mine. The problem with all the boxes I’d tried to fit myself into was that it meant trying to carve myself up into borders; being a first-generation immigrant, borders were something I’d spent my whole life crossing. Sticking to them wasn’t something I did, and as soon as I stopped trying to do so with my dress sense, I started to feel more comfortable. Mixing Indo-Western culture was how I’d grown up. Harem pants and churidars alternate with jeans and leggings. I attend formal dinners and parties in my pheran or kurta as often as in a dress. More often than not, people compliment me when I mix-and-match my Indo-western wardrobe, and it’s gratifying in the way that it always is when people hype up your outfit.

But more than anything, when I pair my jeans with a kurta, it’s a long, overdue statement to myself that I’m finally comfortable presenting what’s on the inside to the outside world.

My wardrobe is a mix-and-match that finally reflects me, not whoever happens to be around me at the time. We’re often taught to think of inner character and outward appearance as different things, but when you let the two work together, you feel more comfortable presenting the most authentic version of yourself to the outside world. I switch pumps for jootis these days without thinking about it, and it’s comforting and empowering all at once to be able to treat the boundaries of fashion as flexibly as I have those of geography and culture.